Well, respect, really. Dr. Sarah-Patricia Breen from Selkirk College is clear on that. The respect to be allowed self-determination. The respect to not be seen as a place somehow inferior, or substandard, or a drain on resources. She said all that last night in Kelowna.

She missed some stuff, though. This, for instance:

That’s a trail sign from Big Bar Lake Provincial Park, kindly informing travellers that bears eat berries. No matter how many times you read it, though, it doesn’t say that the people on whose land the park sits, the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem, love those berries, too, and have been eating them for a long time. The record they have left on the eskers of the park are at least 6,500 years old. That’s a lot of berries. Now, it’s not that Dr. Breen doesn’t know all this, and I’m sure she bemoans this lack of regard as well, but, even so, the whole notion of rural and urban is getting in the way. Even if rural is defined as areas with populations of less than 80,000 people, with degrees or rurality right down to small communities of 100 people or so, as Dr. Breen elegantly delineated it, the inclusion of Indigenous people in that rurality, while excluding their presence in the berry patch, is problematic. Also problematic is the exclusion of this guy catching some rays on a cold September day.

He’s as much a member of the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem community as the bear in the sign above, yet “that’s not what rural means”rural” misses them both. It means “people who don’t live in a town,” and it dates from the 14th century in France and England, and much earlier in Rome. In other words, it is a term used to describe governmental organization of a certain kind centralized in towns, and defines the people who live in smaller settlements by the landscape they live in, which is, by definition, subordinate to towns, and by their “rustic” manners (again, defined by towns.) It doesn’t include this gang:

Ant Lion traps.

Since I was a young man I’ve held that what is termed “rural” and “landscape”are forms of civic space, as much as urban spaces are. This grounding has made its way into my new book, The Salmon Shanties. You can see some of it here looking up to Snowy Mountain from the Ntamtqen Community Garden in Smelqmex country.

Civic Space. Not Rural.

So is the garden. It appears at first as an import of technologies, but that’s what Dr. Breen was hinting at: communities get to define themselves.

Ntamtqen Community Garden.

To the Smelqmex, it is “the meeting place of our ancestors.” There’s more going on here than technology or government, rural or urban. Here’s a community member:

In English, a language that observes this place, she is the “onion” that lowers her head, and raises and lowers it in the wind. She is all about prettiness and contemplation and bashful flirting.

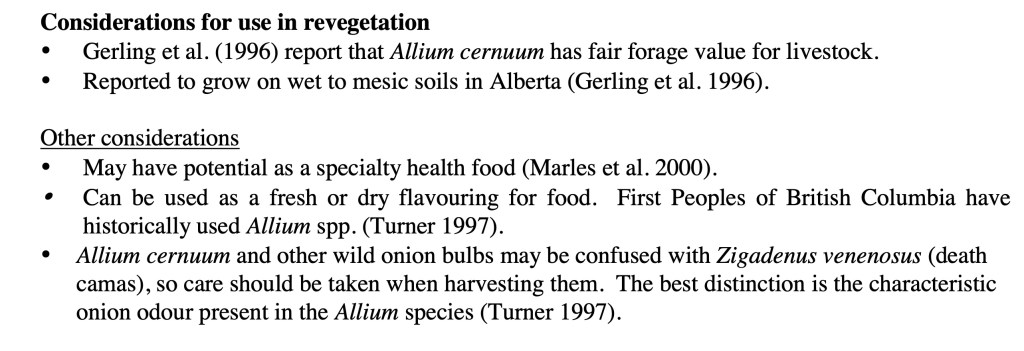

In nsyilxcen, a language of humans in this place, she is xlíwa?, the one that shakes free and falls out. She is all about seed and how to gather it. In both conceptions, there is grace and mystery. In one, she is actively communicating. Here’s how the government, the same settler cultural organization that sets rural and urban parameters, talks about xlíwa?:

There is a certain irony here. The name xlíwa defines the species adequately: the one that shakes free and falls out. Her seeds do, at any rate. Death Camas doesn’t. Isn’t it time to teach native languages in school? It would break down the rural/urban thing. Until then, I suggest that we have a third space: Rural and Urban, for settler government conversations, and another term, an Indigenous one, for the space on which they are writing their settlement narrative and which is both and neither. What settlement culture calls “wild” space or “wilderness” isn’t.

Young Loon Rising

It’s just not rural or urban. We live there.

Categories: Arts, cartography, Ethics, First Peoples, Land, landscaping, Nature Photography

Dear Harold, As usual, I cannot remember my passwords, etc., so here is my comment:

Harold, I’m not sure I entirely understand you, but the practice of putting a label on a place as if it is separate from all that dwell therein (including rock, sand, etc.) does seem faulty to me. I have a similar experience with the word “farm.” We have “farm status” (based on farmgate sales), but I also think that our garden is our farm, or–more precisely–we don’t have a farm, but we *live *a farm. FYI, 80+ acres of our deeded land is not protected in a conservation covenant.

Shalom/Salaam, Curt

LikeLike