After the mountain men from St. Louis braided themselves into Cascadia and competition between the USA and Britain cloaked itself in the form of mercantile competition between the American Fur Company of St. Louis and the Hudson Bay Company of Fort Vancouver used the land and her people as pawns, and after this disrespect exploded at the Rendezvous at Pierre’s Hole in 1832, the next attempt at braiding the land west of the mountains came in 1838. The Catholics were in town.

Photo : Le Père Pierre-Jean de Smet au milieu de représentants des tribus Colville, Tête-Plate, Kalispel et Coeur d’Alène (1859). Source.

It wasn’t exactly news. After all, it had been foretold in dreams among the Cayuse’s cousins, the Nimíipuu, including by the prophet, Tawis Waikt, in 1820:

“My spirit tells me that this earth is going to be turned over, and the koq álx (buffalo or cattle) is going to be all over this country, and there will be no more vacant land as there is today.”

Tawis Waikt

Other prophecies came from songs. One translated by the Nimíipuu singer Many Wounds is cataclysmic:

“All people, and animals! Creation as existing to be overthrown, destroyed! Buffalos exterminated! Elk and deer fenced, confined. Eagles caged from flying! Indians confined to narrowed bodies of land. Liberty and happiness broken and shortened.”

Many Wounds

Another is apocalyptic:

“Rough places, crooked places of Nature’s beauty, some one will smooth and straighten. Flowers looking upward will no longer bloom. Forests will melt away, game disappearing. Rivers to be held back and lessened. Salmon no longer plentiful for the tribes.”

Many Wounds

Others are eerily specific, such as the prophecy related by Silimxnotylmilakabok (Bighead, so possibly a Syilx man) to Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1841:

“Soon there will come from the rising sun a different kind of man from any you have yet seen, who will bring with them a book and will teach you everything, and after that the world will fall to pieces.”

Silimxnotylmilakabok

The Couer d’Alene spent a century looking for them. Then one day they showed up.

“Here we are,” said the Catholics.

“We knew you were coming,” said the Couer d’Alene, proving that they hadn’t really been hiding behind the mountains all this time. For the full story behind the prophecies, please go here: https://okanaganokanogan.com/2022/12/10/38-ravens-prophecies-the-war-of-1812-and-the-old-northwest/

The prophecies predicted that “the black robes” (Catholic priests) would bring peace between the Couer d’Alenes and warring tribes on the plains, armed only with crooked sticks (croziers, or pastoral staffs). Well, maybe, but other peace proved elusive over time:

Eventually, peace would have to be kept by hanging De Smet to foster inclusion at the University of St. Louis. Source.

The Wishrams went further. As recorded by James Teit, they prophecized rifles:

Soon all sorts of strange things will come. No longer (will things be) as before; no longer, as will soon happen, shall we use these things of ours. They will bring to us everything strange ; they will bring to us (something which) you just have to point at anything moving way yonder, and it will fall right down and die.”

An un-named Wishram prophet.

Others predicted — pretty close to the money — that everyone would die. Even the plants and animals that were human spiritual supports in the world would vanish. There’d be no more camas bulbs, no bitterroot, no elk, no mule deer, no bears and no fish, and so it almost came to pass.

Bitterroot in the John Day Country: rare but not gone.

Settlers expressed surprise at how it all worked out.

Settlers: What, no more fish? After decades running the fish wheel at Pillar Rock, that scooped a million fish a year out of the main stream of the Columbia? It’s the Apocalypse!

Other Settlers: No more bears? When Lewis and Clarke had shot dozens while camped at Kamiah, waiting for the snow to melt so they could cross the mountains against Nimíipuu advice?

All the Settlers together: What is God’s plan for us?!

Raven: Krak! Krak! Krak!

Discussion between settlers and ravens, recorded by Harold Rhenisch, December 6, 2023.

But the Couer d’Alene and the Nimíipuu had seen it coming. No surprise for them.

The Camas Prairie south of Lapwai, planted in wheat to honour God.

No camas bulbs, though.

Here’s one in bloom:

No wheat, though. Source.

In 1838, Father Modeste Demers, the original fulfiller of this prophecy, settled in French Prairie. Demers was a son of the Beaupré, the cradle of Quebec habitant culture along the St. Laurent south of Quebec City.

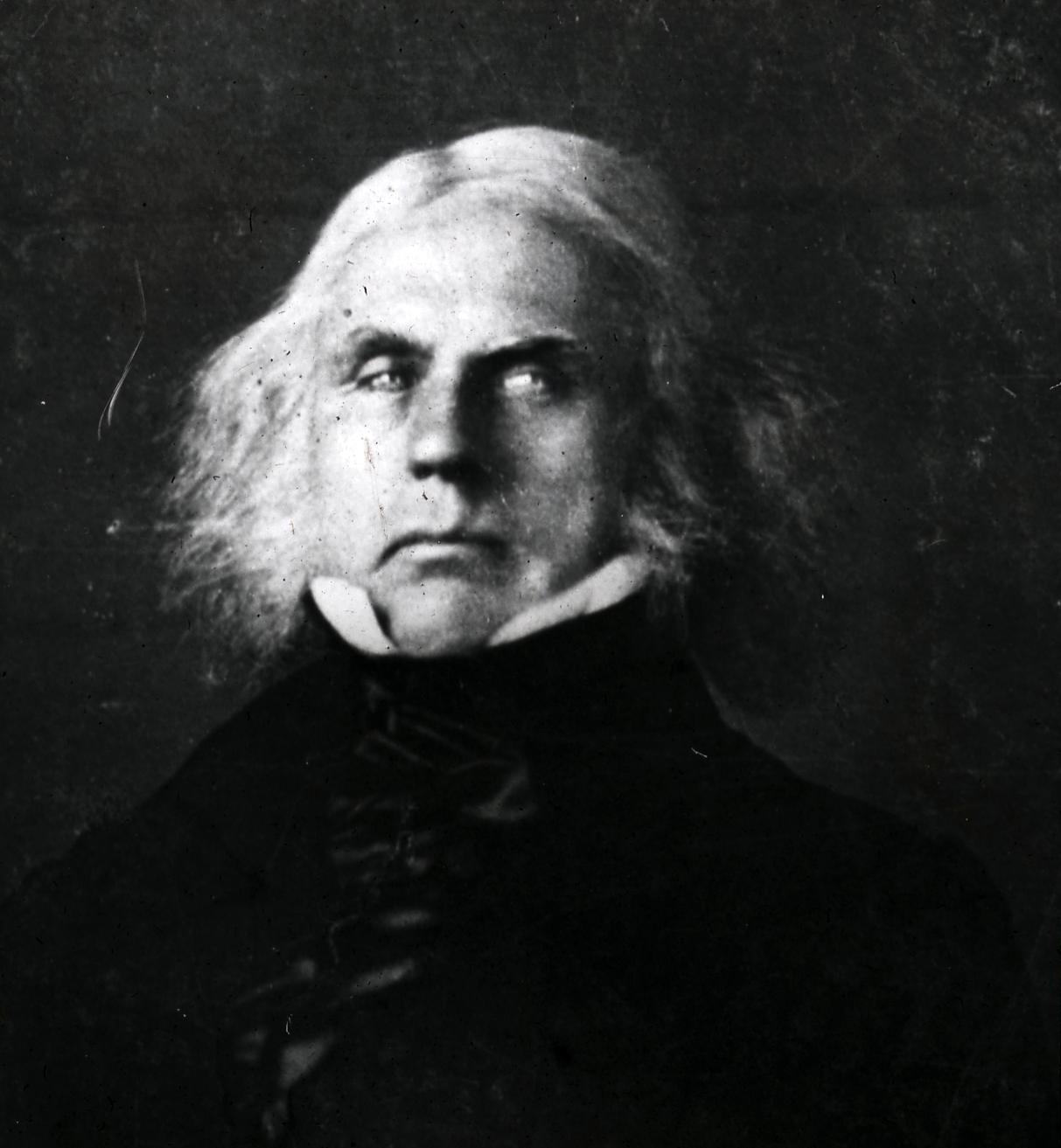

Modeste Demers

Demers was ordained as a Jesuit in 1836 and worked — briefly — as a missionary on the Red River. After two requests from Canadians retired from the Hudson Bay Company and farming with their Indigenous wives on the French Prairies, he went west to save their souls, with the goal of saving Indigenous souls on the side. This wasn’t exactly a clear-cut plan. It had a couple problems:

- The Canadians didn’t really want the church directing their lives. They just wanted the social legitimacy that came from the social status the church could confer: marriages, burials, baptisms, and so on, all of which were important to legitimize their claim to land and property and to pass them on to their children. Otherwise, they would remain outside the law. That left the church to finance itself.

- Indigenous people didn’t want the church directing their lives. They wanted the same thing the Canadians did, with the addition that they wanted the church to provide a buffer that would protect them from aggression from incoming immigrants.

- The church couldn’t own property, so was unable to finance itself by setting up a mission in the Spanish style. Well, not legally, anyway.

- The population of French Prairie and the Willamette Valley it sits within was rapidly Americanizing, with people who viewed French catholics as national enemies (which at one time they had been).

As a result, the church was rendered relatively ineffective, subsumed into a rising American culture and trying to survive within it in the same way that Canadians and Indigenous people were. As an example of how the Church’s ability to project power and protection eroded, fifteen years later, in 1852, an early schoolteacher in Seattle, Kate Blaine, wife of the settlement’s first Methodist pastor, was incensed that the territorial legislature was contemplating granting the vote to “half breeds.” To her thinking many “Indians” would fall under the definition and would gain the vote, and, she wrote,

“You talk about the stupidity and awkwardness of the Irish. You ought to have to do with our Indians and then you would know what these words mean.”

Kate Blaine

Regarding her terms “stupidity” and “awkwardness,” Mrs. Blaine explained that “Indians” were lazy, smelled, went around naked in warm weather and that their children “know as little of shame as the beasts of the field.” Apparently, the shame was her own and by the sounds of it proudly embraced. That most European men in the territory had children with Indigenous wives, suggests that she was not in favour of the integration of Washington’s history with a perceived White future.

Kate Blaine in 1880.

Catherine Blaine was one of the original 100 women who initiated the women’s suffrage movement in the United States. Then she moved West. During the 1855 Yakima (Puget Sound) War, her husband gave up their church as a blockhouse. Immediately afterward, she and her husband moved to Oregon, to continue their parish work there. Unlike the Catholics, negotiating between Indigenous and White worlds was not part of either her world view or her future. A little later in this discussion, we will see Father Pandosy’s church burnt down because he had sided with the Yakama.

These were the choices offered to everyone at the time, in a culture of rumours, media manipulation, populism and fear. Sound a lot like the world of today?

If by Mrs. Blaine’s “stupid” and “awkward” Irish, she meant that they were Catholic (a likely enough reading of an immigrant people who retained ties to non-American lands and institutions), she likely had her sights on the catholicization of “Indians” as well. Such imported attitudes from her native New York (and the high numbers of Irish settling there as refugees from the potato famine at the time) spoke of her separateness from the land and its people, as well as general fears of cultural replacement commonplace during periods of mass migration, such periods, as, well, today. As the Huffington Post reports:

Note the accompanying ad for a white vacation in, what is that, Mexico maybe? Troubling stuff. (Screen capture on December 7, 2023).

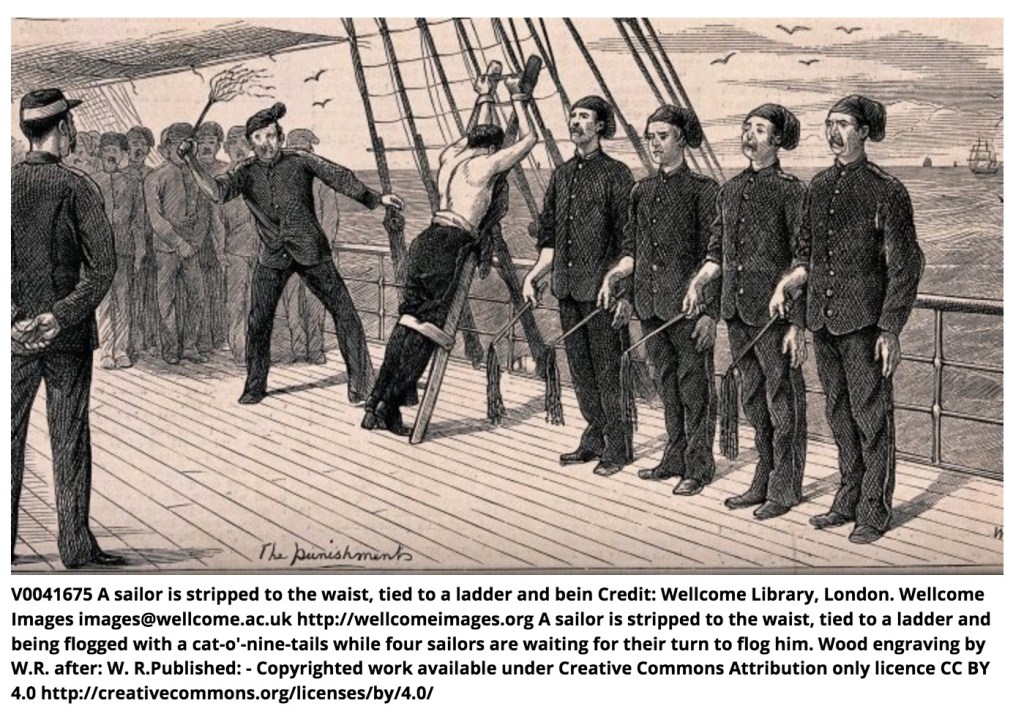

Such racialized expressions of confusions about settlement, privilege and place weren’t limited to American sensibilities. (And why should they be? America is England, just in a new form.) For example, when John Ball opened the first school for “Indians” and “Half Breeds” at Fort Vancouver in 1832, he reported that his two dozen pupils spoke Klickitat, Nez Perce, Chinook, Cree and French. Only one student spoke English, and he objected about how the school was being run. Fair enough, too. English was taught by pointing at objects, saying their names, and asking students to repeat simple sentences by rote. Seemingly, the boy’s good reasons for his objection struck a chord, because Chief Factor John McLoughlin, whose own sons had a native mother, responded by taking the “Indian” boy outside and thrashing him until he agreed to do things Ball’s way. Shame and abuse, it seems, were not only how to whip sailors into shape…

… and in the US Navy, too…

…but the way to make boys White.

Dr. John McLaughlin. Maybe not a good father, really.

McLaughlin’s (Catholic) son David resolved this White-Indigenous divide by leading Oregon boys up through Syilx territory in 1858, against the US Army’s prohibition (ironically and prophetically in place to prevent armed conflict and revenge killings). David McLaughlin was 37 years old, and a veteran gold miner from California, where he had reportedly made (and presumably lost) $20,000 in gold. His illegal journey to new gold fields, based on a report from the man who discovered them, another man racialized by the end of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Oregon, a Hawaiian called William Peon, ended in an ambush on the Okanogan River south of Tonasket, and the eventual disenfranchisement not of White settlers, such as the Oregon boys led north by McLaughlin, but of the Smelqmex and their cousins the Chelans, the likely perpetrators of the defensive ambush.

McLaughlin’s Canyon Ambush Site

In other words, the consequences were huge. Think about it this way: the beavers that drew métis men to Pierre’s Hole in 1832 to assert their status in an increasingly White society, were now replaced with gold. Not only that, the beavers were replaced with White men themselves, who the sons of the fur trade now led to the gold, just as they had been leading Americans west to Oregon for years. Like the beavers (and Oregon), the gold was on Indigenous territory. The mythologies were different, though, in both cases of exploration and settlement. More money was involved now, with more of a technological foundation. Now White men felt they could settle the land (in Oregon) and dig up the treasure themselves (in Nlaka’pamux Territory) rather than exploit Indigenous and Iroquois men to do so, as was the practice in the fur trade. You didn’t need an organization behind you. You could do it on your own. In short, many thousands of men felt a sense of haste in making a conversion to White power, whether as métis men trying to maintain their former valuable intermediary status, White men chasing gold to buy White power, or Indigenous men wanting the power of the church so they could mediate with explosive White culture just as they saw the Church do, or thought they did, at any rate. In other words, much of this story is the narrative of how the Church lost its intermediary status itself, just as the compromises Modeste Demers had to make in French Prairie or David Blaine had to in Seattle just to survive, and which Father Pandosy refused to make, only to become an outcast.

Next, we’ll look at Methodist compromises and how pressures on that church fueled war as well. Until then, a reminder of the country itself.

An Ancestral (captikwt) Story of the Ancestor Sen’klip near Nighthawk on the nmelgaitkwt.

.

Categories: Ethics, history, Pacific Northwest, Spirit