The War of 1812 saw Britain, Indigenous peoples and the United States fight on both sides of the Great Lakes over independence and expansion: US independence to trade with Napoleonic France, recognition of its citizens as Americans, and expansion into Indigenous lands in the Northwest.

A Bit of a Self-Involved Business, Really

Canadians often say they won the war, because at the end Canada still existed. Americans are just as proud, for the same reasons. Both fighters were exhausted, so they made up:

They decided they could share.

And note the “kindred interests.” Keep a note of those.

Here’s how UShistory.org puts it:

The War of 1812 came to an end largely because the British public had grown tired of the sacrifice and expense of their twenty-year war against France. Now that Napoleon was all but finally defeated, the minor war against the United States in North America lost popular support. Negotiations began in August 1814 and on Christmas Eve the TREATY OF GHENT was signed in Belgium. The treaty called for the mutual restoration of territory based on pre-war boundaries and with the European war now over, the issue of American neutrality had no significance.

https://www.ushistory.org/us/21f.asp

It goes further, too, like this:

In effect, the treaty didn’t change anything and hardly justified three years of war and the deep divide in American politics that it exacerbated.

https://www.ushistory.org/us/21f.asp

That’s hardly fair. Indigenous peoples, fighting to preserve their independence south of the Great Lakes, were decisive in the conflict. This man, more than most:

As the Canadian Encyclopedia relates:

The conflict forced various Indigenous peoples to overcome longstanding differences and unite against a common enemy. It also strained alliances, such as the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy, in which some nations were allied with American forces. Most First Nations strategically allied themselves with Great Britain during the war, seeing the British as the lesser of two colonial evils (see Indigenous-British Relations Pre-Confederation) and the group most interested in maintaining traditional territories and trade.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/war-of-1812

It didn’t go well.

Two Shawnee brothers, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, implored Indigenous peoples to unite in order to defend their dwindling lands against the growing incursions of American settlers and the United States government. The promise of such an Indigenous state never came to fruition. During negotiations for the Treaty of Ghent (1814) that ended the war, the British tried to bargain for the creation of an Indian Territory, but the American delegates refused to agree.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/war-of-1812

In short, they lost all of their land, the very reason for fighting. Not a lot of happiness in the image below:

Six Nations Veterans of the War of 1812.

Six Nations Warriors who fought with the British. Photo taken in July, 1882. (right to left) Sakawaraton – John Smoke Johnson (born c. 1792); John Tutela (born c. 1797) and Young Warner (born c. 1794).

(Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada-C-085127) Note the tomahawk and the short swords for close-in work.

It was the end of the world.

For Indigenous peoples living in British North America, the War of 1812 marked the end of an era of self-reliance and self-determination. Soon they would become outnumbered by settlers in their own lands. Any social or political influence enjoyed before the war dissipated. Within a generation, the contributions of so many different peoples, working together with their British and Canadian allies against a common foe, would be all but forgotten (see Indigenous Title and the War of 1812).

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/war-of-1812

Perhaps you don’t have to ask who the common foe was now?

For the British and Americans, this was a war fought as part of the Napoleonic Wars. For Indigenous people, it was part of a struggle that predated the War of 1812, and lasted far after its close. In previous posts, I showed how American and British fur trading companies manipulated access to Indigenous people to gain access to land. In following posts, I will show how this struggle came to include all Canadians in the Columbia District. The results were the same as they had been in Indiana: broken bonds between Indigenous people and their French and English allies, and the replacement of both with American settlers. Canada retreated north, much as the Iroquois had in Indiana. Well, with the figurehead of a ship floating through the air without her ship, wouldn’t you?

The Goddess Columbia on the Move

American Progress, by John Gass. Note how an ideal of whiteness precedes the sun.

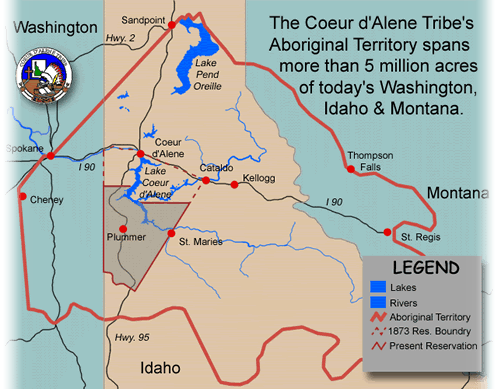

But those are just British or American narratives. For Indigenous people, this catastrophe was foreseen long before the United States or Canada became nations. Pierre Jean de Smet, historically the first Jesuit in Montana (1841), reported that around 1740 (three decades before the creation of the United States, seven decades before the War of 1812, and a century before de Smet), a raven circled over a Schitsu’umsh village, perhaps on Lake Coeur d’Alene, which held 200 lodges and most of the population. We don’t know how the date of 1740 was arrived at, but here is Schitsu’umsh territory:

The map is a bit sad. Schitsu’umsh territory went north of today’s USA-Canadian border, too. There was no border.

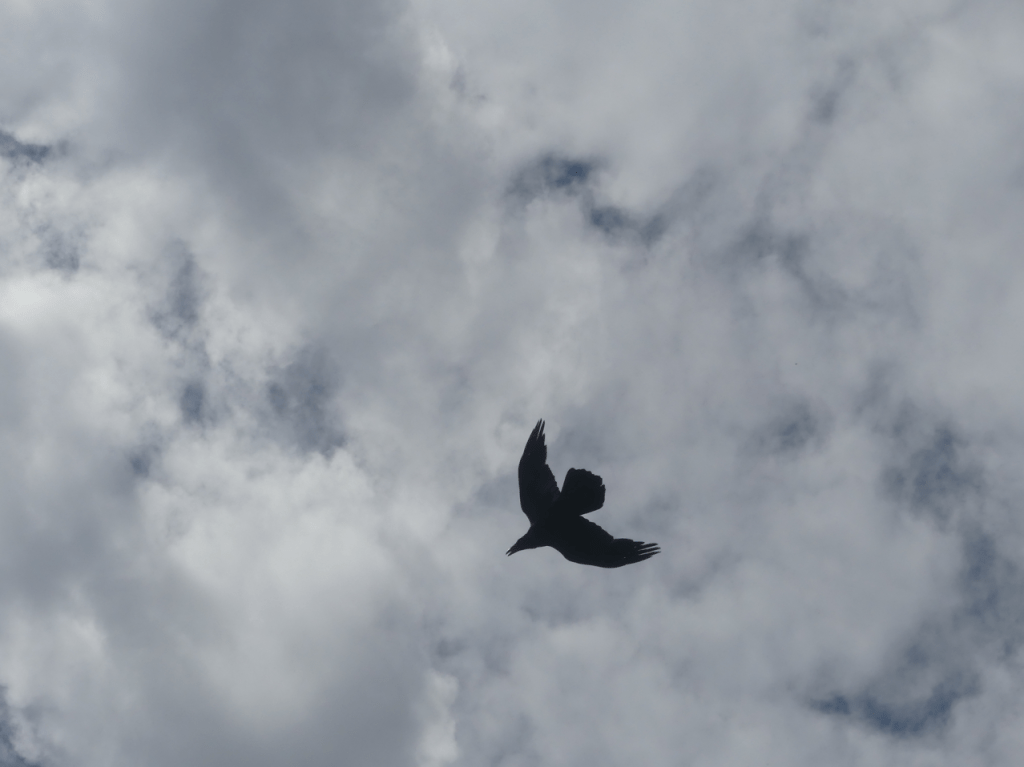

Ravens are always watching what humans are up to and croaking about it to anyone who will listen in the stick, pebble, dead tree, wind and feather language of ravens.

You’ll get dizzy watching them, circling around and around, so, as the story about the story goes, in 1740 (?) most people didn’t watch. They knew better. Afterwards, Chief Circling Raven asked people if they understood what the raven had said. No, they had not, so he told them:

“Evil times are coming. An enemy is on the way, stronger than any you have ever known. It will surround you. Right now, here, in your illahie, in this country that is all you are, it has seen you from across the earth. Your blood will spill. You will weep and wail and cry. Bring your strength together. Do it now. The enemy will not come first. First, three ravens will show up. They will teach you how to live through the attack.”

Chief Circling Raven, 1740, purportedly

It has all the markings of a wooden translation from the Hudson Bay Company trade language Chinook Wawa, but the meaning is clear enough: people were not ignorant of what was coming their way. We don’t know if a raven actually did say all this, but in another telling of this story, these three ravens had black shawls and white heads. So, that’s more like eagles than ravens, really.

Not a raven,

We should, however, treat the story with some care. After all…

An Analysis of Coeur d’Alene Indian Myths, by Gladys A. Reichard, American Folklore Society, 1947

Even the chief who purportedly told this story is part of it. His name, after all, was given as Circling Raven. And when ravens circle, they see all the world.

Not an Eagle, really,

In Chinook Wawa, the common language of the Pacific Northwest, ravens see konaway kah, everywhere. And if they happen to be a crow, a kah kah, announcing “There! There!” and not a raven, who says hello with a “Klook!” as crooked (klook) as his beak, when ravens circle they do see the whole world…

Kalook!

…and they announce it, just as the chief did. In fact, just looking at them says it all. Seeing them is to know.

That is, if the teller of the tale was a chief and not a bird, or if Circling Raven really was his name. It may not have mattered. In Chinook Wawa, it was a yiem, a telling, that became yiem, a tale, after it was told, and it had a certain language it had to follow, just as Christian stories do. Moses, for instance, was not the first baby to be found in a reed basket on the Nile, nor was Jesus the first messiah or god to die on a cross. These were essential parts of any story, which made it true, just as a reference to individuality is today. The following discussion of Schitsu’umsh storytelling hints at how all this works:

An Analysis of Coeur d’Alene Indian Myths, by Gladys A. Reichard, American Folklore Society, 1947

So was it a kahkah, a crow, cawing and crowing to a village of animals and kalakala, birds? Or kawkaw kalakala, bird song? There was not a huge difference. If the crowing was one to animals in the land, a sense of space that stretched to the very beginnings of time, before the age of humans, it applied just as well to the age of humans that grew from it, but with the voice of the land itself, where all oral stories begin and return. The chief, after all, was probably a raven and a man, because in this conception land, illahie, was human identity because it was a yiem, a story, with set characters over a couple thousand generations. Each person was its present telling. Being embedded like that was history — not the novelty of new occurrences that British or American culture calls historical time. This is not even an exclusively North American Indigenous conception. The Wiccan poet Robin Skelton long argued that the Old Religion in Europe, the earth-based religion now called Wicca or witchcraft, saw the world as a series of stories. One sat perfectly still as they washed over one. A Jesuit observer like de Smet would want to put a date to it all, but that doesn’t mean there originally was one in that sense. So, was it a prophecy? Or just straight talk? Or was this how a man read the flight of ravens circling above the corpses of people dead from smallpox, that also preceded European presence? Here’s a timeline of Smallpox in the 18th and 19th centuries to worry between your mind’s teeth:

- 1763 South Carolina

- 1764 Charleston, MA & Newport, RI

- 1764-65 Creek, Chickasaw, & Choctaw in Georgia

- 1765 Annapolis, MD and seven nearby counties

- 1765-66 Philadelphia, PA

- 1768 Reading, PA (60 children died)

- 1768 Southeast Virginia

- 1769 Philadelphia, PA

- 1773 Philadelphia, PA (300 died)

- 1775 New England.

- 1775 Rampant in the Revolutionary War, among British, American and Indigenous troops.

- 1775 Columbia River, brought in perhaps by fur-trading ships, then spreading upriver

- 1779 Great Plains.

Lakota Sioux. Winter count by Battiste Good Year, drawn in 1779–1780. Note war in 1779, and Smallpox lasting into 1781.

- 1780 Brought to the pueblos of the Southwest by trade with the Shoshone.

- 1782 Brought to Hudson’ Bay Company posts by contacts with the Shoshone.

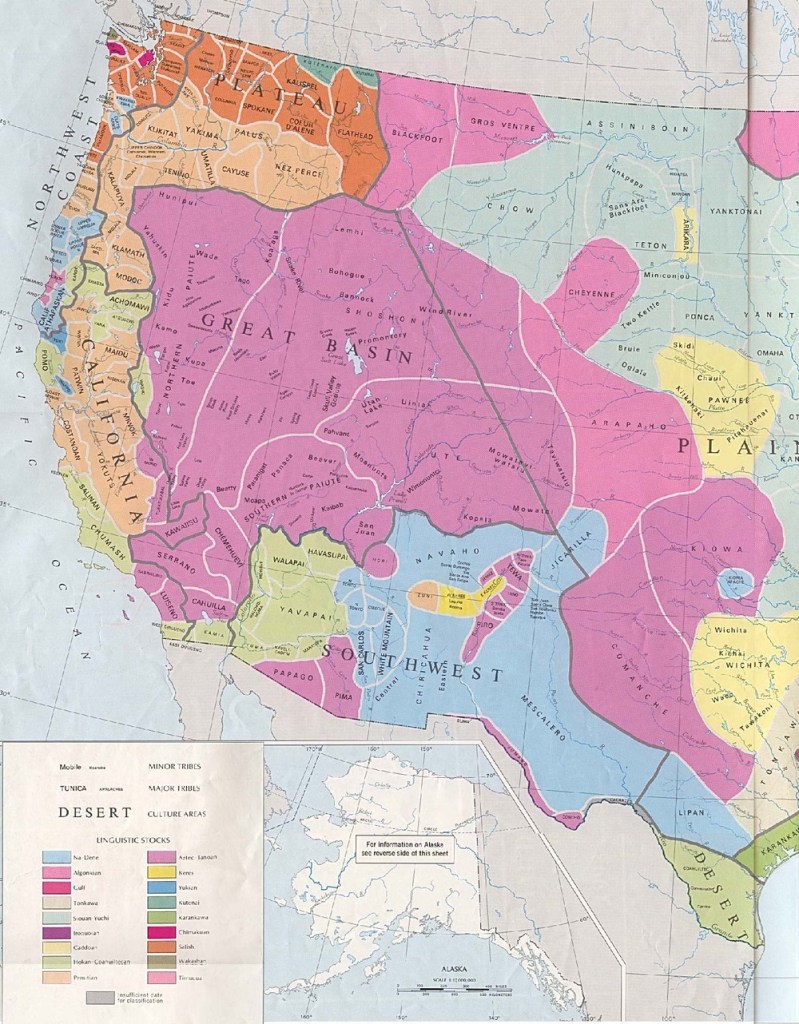

Note How Shoshone Territory meets Flathead and Blackfoot Territory. This is a colonial map. Before 1787, the Blackfoot territory on this map, and hundreds of kilometres to the north, was Shoshone. In the process of invasion, huge numbers of Shoshone children were captured as slaves and became Blackfoot. This was alliance by force. One would be careful not to attack one’s children later. In return, your adult children could help you a bit through trade. Invasion was driven by the collapse of the fur trade in the Far North and the move of the Cree onto the plains, fueled by access to horses and rifles, which became essential to survival. By the way, if you think that map is busy, look at what Wikipedia serves up (and then skip ahead to a summary):

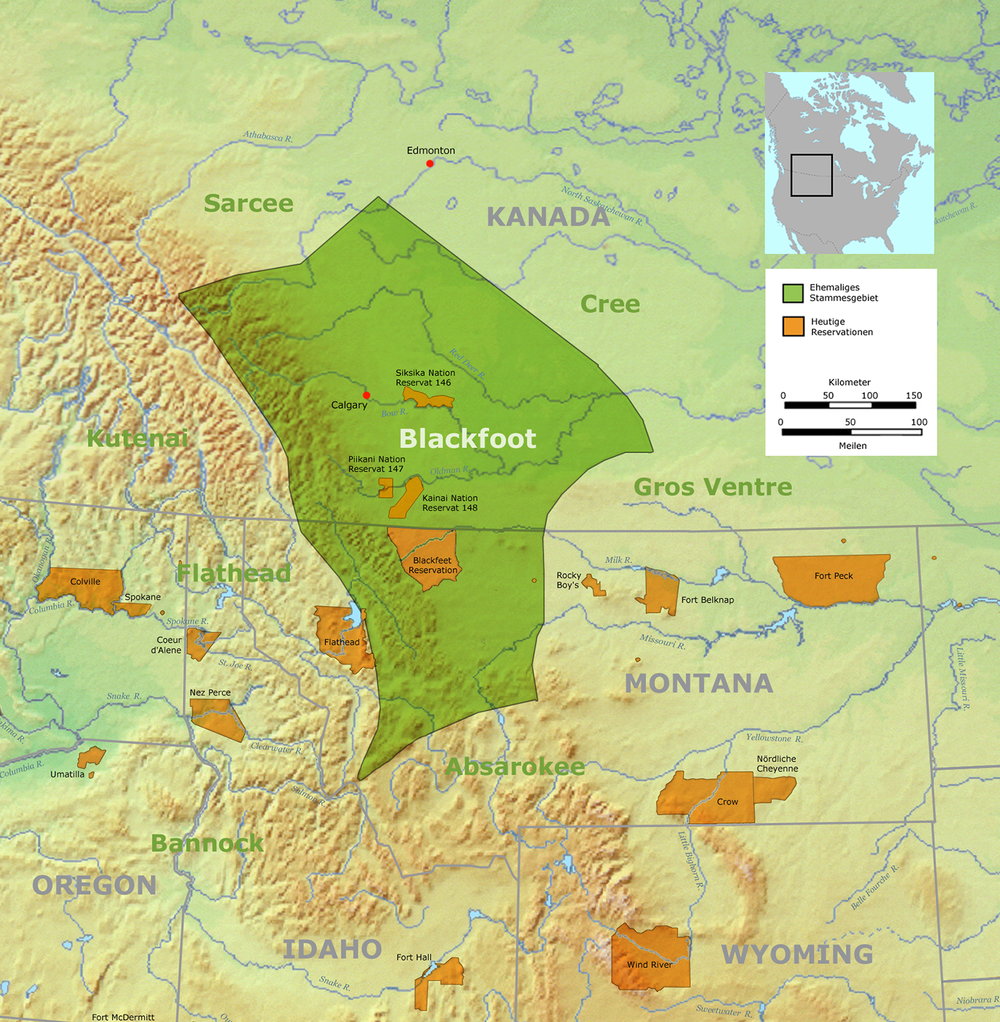

The Niitsitapi were enemies of the Crow, Cheyenne (kiihtsipimiitapi – ″Pinto People″), and Sioux (Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota) (called pinaapisinaa – “East Cree”) on the Great Plains; and the Shoshone, Flathead, Kalispel, Kootenai (called kotonáá’wa) and Nez Perce (called komonóítapiikoan) in the mountain country to their west and southwest. Their most mighty and most dangerous enemy, however, were the political/military/trading alliance of the Iron Confederacy or Nehiyaw-Pwat (in Plains Cree: Nehiyaw – ‘Cree’ and Pwat or Pwat-sak – ‘Sioux, i.e. Assiniboine’) – named after the dominating Plains Cree (called Asinaa) and Assiniboine (called Niitsísinaa – “Original Cree”). These included the Stoney (called Saahsáísso’kitaki or Sahsi-sokitaki – ″Sarcee trying to cut″),[22] Saulteaux (or Plains Ojibwe), and Métis to the north, east and southeast. With the expansion of the Nehiyaw-Pwat to the north, west and southwest, they integrated larger groups of Iroquois, Chipewyan, Danezaa (Dunneza – ‘The real (prototypical) people’),[23] Ktunaxa, Flathead, and later Gros Ventre (called atsíína – “Gut People” or “like a Cree”), in their local groups. Loosely allied with the Nehiyaw-Pwat, but politically independent, were neighboring tribes like the Ktunaxa, Secwepemc and in particular the arch enemy of the Blackfoot, the Crow, or Indian trading partners like the Nez Perce and Flathead.[24]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackfoot_Confederacy

Here’s the summary:

Blackfoot Territory at the End of the Colonial Period and Today

Summary: Everyone surrounding this militarily conquered and fiercely protected territory was a mortal enemy. Alliances were made between nations to the west (like the Secwepemc) and the east (like the Sioux). Decimated by Smallpox and catholicized by Kahnawake Iroquois, the Schitsu’umsh were largely trading partners.

The smallpox devastation loosed by the American Revolutionary War continued:

- 1782 Brought back from the plains by Schitsu’umsh buffalo hunters.

- 1782 The Strait of Georgia, at the mouth of the Fraser River.

- 1824 Columbia River.

- 1853 Columbia River.

Populations were decimated. In this regard, it is worth noting that Schitsu’umsh buffalo hunters also traded for horses and rifles. The horses came from the Shoshone, cousins of the Cayuse, around 1730. The rifles were originally traded down from Rupert’s Land.

Rupert’s Land: the HBC stronghold. The western edge is Blackfoot Territory (And the Rocky Mountains).

Trading trips to York Factory could take a year, which was a strong incentive for the Blackfoot to monopolize trade with the Kuten’axa across the mountains and to block the Northwest Company from supplying them with rifles. They were powerful, united people.

Big Snake, Chief of the Blackfoot Indians, Recounting his War Exploits to Five Subordinate Chiefs, 1851-6, Paul Kane.

Note the trade beads sewn into their clothing. Source: https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artwork/big-snake-chief-of-the-blackfoot-indians-recounting-his-war-exploits-to-five

The Cree wanted contact with Rupert’s Land to go through them. The Blackfoot welcome the Northwest Company, as a workaround, while controlling trade across the mountains. All in all, it was kind of like the interface these two groups attempt with trade with China today:

It’s not all that crossed the mountains from Schitsu’umsh expeditions:

A bit of a timeline will help illustrate just how little of a Euroamerican story this is. For context, the 1740 that Demers gave to this story is the year the Cree (who had been in contact with Europeans since 1611) moved down out of the North onto the plains and began to control trade with the Hudson’s Bay Company through the Iron Confederacy. If they had wanted to control trade in an oral culture, a story would have helped. Same for the Blackfoot. A story of danger, destruction and threat would have been useful to bind people in place, as it continues to be today.

June 2020. President Trump admires his border wall.

The Kutenax’a story above doesn’t jive on a timeline. Something has been conflated or left out. However, before we get to that, read on:

Actually, she had two daughters and a son. To see what’s going on and to build a timeline, we need just a little more info. Here goes:

For Cahnawaga, read Kahnawake.

Most likely, Ignace Big Knife was out in the bush. Where else? At any rate, Mary stayed, apparently, and became immersed in Catholic culture. And one more detail, this time information about Mary’s daughter:

So, the girl came west at 14, on what was a perhaps a 6-month-long journey, with her brother and sister. We’ve already been told that her mother came, too. We’ve already been told as well that David Thompson and his boatman Old Ignace found already-Catholicized people in the region in 1808. If the girl was the middle child (it seems likely), then the latest possible date for her arrival was perhaps 1800, and the latest possible date for her original capture perhaps 1780. 1740 is not out of the question, though, given the movement of the Cree and Blackfoot in 1740 and that this guy, as jesuit trained as anyone …

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye.

Portrait by Edgar Samuel Paxson (1912)

…went west in 1740, and his sons, part of his team, arrived in Montana that year. It’s possible, that the story of coming priests came from them, or from the two men they left behind to learn the Maidan language. They would, after all, have been of great interest and would have had an interest in opening imaginations to a coming European presence. At any rate, we don’t know, but we do know that dates and occurrences don’t exactly match here. Here’s another story, one that places Mary and her son Eneas in the Kootenai Illahie, but much later. This is her son, Eneas, a Flathead pronunciation of Ignace, in itself an Iroquois pronunciation of Ignatius, or St. Ignatius, a common Christian name given to children of Kahnawake at baptism:

Young Ignace was among a group of some 24 Iroquois who settled among the Flathead in the Bitterroot Valley sometime between 1812 and 1828. Having been preceded by other Iroquois converted to the Roman Catholic faith prior to coming west with the fur trade, the group was led by Ignace Lamoose and thought to have comprised a separate migra- tion perhaps encouraged by reports from earlier Iroquois fur traders. Ignace Lamoose, also known as Old Ignace to distinguish himself from the younger Ignace in his group, married into the Flathead tribe and taught them numerous Christian beliefs and customs.

http://www.swanrange.org/documents/Lineage_of_Chief_Aeneas.pdf

Ignace Lamoose was with David Thompson in 1809, at Flathead House, and at Astoria that summer. At some point, presumably the return trip, he left the expedition to settle among the Salish, and showed up later at Fort Nez Percés with his Flathead wife. He also made a trip back East to bring 24 others to settle with him. Now we have three stories running parallel to each other:

- this is the trip that brought Eneas and his sister, and on which their mother presumably perished. The name Big Knife came from his father, in a familiar pattern of inheritance.

- this is the trip that brought Eneas, Big Knife, to the West; his wife was never a part of the Kahnawake community.

- there is no direct connection between the name Eneas, Big Knife and a Kutenax’a girl taken east sometime between 1740 and 1780, although the stories now overlay each other.

Chief Aeneas (Eneas) Paul

Other stories are possible, too:

- Ignace la Moose was the first Big Knife, and went back to get his kids. It would explain why he stayed in the first place: he knew where he was going.

- La Moose had been there before, but was not the kids’ father.

- And this:

Which puts him at the centre of the story. And so on. We could go on like this for a long time, but the real story would vanish from the effort. Let it just be said that generations before de Smet arrived in Flathead country, a girl had been taken back to some French encampment as a slave then a wife, became catholicized, brought her children back on some Iroquois expedition, and spread words of warning, or:

- de Smet made the whole thing up.

Pierre-Jean de Smet

The latter is possible but perhaps too simple. There are other prophecies, among the Flatheads, the Colvilles and the Syilx, all who had known priests were coming long before they id. And there’s this:

Conjecture follows:

And all in all, it sounds like catholic propaganda:

Still, the conclusion fits at least the arrival of Ignace Lamoose:

My point with all of this is to illustrate how a historical story, approached by an imagination built up in the patterns of oral stories, which return to a stereotype in a distant past living on in the present but accessible only through dream and bodily knowledge, such as understanding the thoughts of a raven by watching a raven or calling people birds and animals, can bind history into the land. It offers an alternative history of the Columbia Country and a way forward that includes it. Given that extant history does not include the pressures of the War of 1812 or the American Revolutionary War on the movements of people in the far west, or the roots of this story of dispossession and return as modern people, I’ll be following this one for awhile, as it ripples further and further into recorded histories in which its power has been overlooked. Here, for instance:

The War Goes On in the Métis Settlement in the Syilx Illahie of sx̌ʷəx̌ʷnitkʷ.

Sometimes, though, it looks like this:

A Grippling Pear in the Canadian Settlement at sx̌ʷəx̌ʷnitkʷ

Or this:

Christmas in the American Settlement in sx̌ʷəx̌ʷnitkʷ

For any of us who are of this land, this is an essential narrative. Unlike the three stories in the three images above, the colonial one, this is the tradition we are descended from. This is the one that tells our story. This one…

sx̌ʷəx̌ʷnitkʷ

Categories: Ethics, First Peoples, history, Land, Pacific Northwest

A very well researched an interesting article! Just a bit of trivia to add: John ‘Smoke’ Johnson earned his nickname ‘Smoke’, during the War of 1812 on the Niagara peninsula. After Newark was destroyed by American forces in December 1813, British forces with Indigenous and Colonial support went across the Niagara River and burned Lewiston to the ground. Then they moved on to Washington and burned down the White House. Johnson was the grandfather of poet Pauline Johnson. Some of her stories and poetry were influenced by the stories ‘Smoke’ told her in childhood. Your article is excellent! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Thanks, Sharon! It’s wonderful to see these details! Can you point me in the direction of info on Smoke?

LikeLike