Back in the spring I pointed out that during the dominance of New France over the West, the Iroquois trafficked in slaves between the Sioux and the French. This transfer of Indigenous slave taking (and alliance making) into European monetary power and social status, across the boundary of the European world in North America, helped thwart this man:

Louis XIV, aka Louis the Great. Painting by Hyacinthe Rigaud, c. 1701. Source

A true blue stocking.

After the Fall of New France, the Iroquois kept up the trade, but eventually only in beavers. Here’s a summary of how these things went, to refresh the story. At its root, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Sioux controlled the expansion of New France (and its threat to their own status as traders) through the Rockies through slave raids on the western edge of New France. Here’s a map of how things stood.

Sioux Territory Within the Blue Sea of New France Shortly Before its Fall. Source.

The Sioux controlled expansion to the west in order to remain privileged traders between the. French and the Indigenous nations of the Northwest. The actual West (the western grey zone above) was isolated through their efforts. A detailed history is here.

To recap, the Sioux gifted the resulting slave children to French officers. As they were improperly integrated into Indigenous culture (although given the opportunity), the officers acted as powerful people often do within an aristocratic society: they turned from the diplomatic potential of these children in Indigenous society and adopted something more familiar: European notions of display. There were, after all, 10,000 courtiers working every day in France’s Palace of Versailles, all vying for status in relation to the sole power in France: the king. Look what happened when diplomats came from the Far East:

Siamese Embassy To Louis XIV, in 1686, original by Nicolas II de Larmessin Source.

They brought expensive gifts. The king showed his fencing leg. Note that the Siamese ambassador, with the gifts, is not leading with his fencing leg. Nor are the king’s courtiers. Tricky stuff. You had to know left from right to play this game.

That’s how a European court worked, so when the Sioux brought captured children as slaves, French officers too far from court to have a hope of getting the attention of the king found the kids apparently difficult to resist (each one was an officer’s annual salary). In a country like that, one watched power. One’s only access to it was through admiration and subordination.

March of the King accompanied by his guards passing over the Pont Neuf in the direction of the Palace, Jan van Huchtenburgh, last quarter of the 17th century. Source.

If one couldn’t get the king’s, through the hopelessness of trying to conquer a continent by Indigenous trade alone, then any attention would do. Unfortunately, these rituals did not carry perfectly across cultures. When the officers (and even governors and bishops in Montreal) translated the children into monetary objects, into labour slaves, they mirrored their own subconscious attitudes to “savage” people, although what they really needed was alliances with the people of Cascadia (a major slave source) instead. The people wanted their kids back and were willing to make alliances. The French, however, drunk on their own status, missed their chance. When the Americans came…

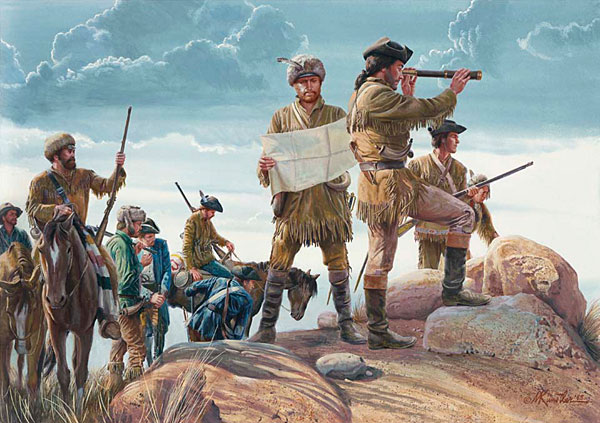

Lewis and Clark Checking a Map to Unmapped Territory

… they sort of blew it, too. They came with a bag of ceremonial trinkets, medallions with the President on them, and even little mirrors, and gave this stuff out to help make alliances. Unfortunately, what they gave away was worthless, but was accepted by people such as the Nimiípuu as being of great worth and cementing permanent bonds between equal nations. For instance, the chief Apash Wyakaikt (Flint Necklace)…

Here he is at the bitter 1855 Walla Walla Treaty Council, which went badly.

…of Asotin Creek and the confluence of the Snake and the Kooskooskie Rivers at today’s Lewiston Idaho and Clarkston Washington…

Asotin Creek Enters the Snake. Photo by Harold Rhenisch.

Efforts are being undertaken to reintroduce the eels, blocked by the Snake River dams downriver.

…received a little pocket mirror, a looking glass, and gained the name Ippakness Wayhayken (Looking Glass Around the Neck), or just Looking Glass, from that. The name, and its ceremonial significance, was handed down to his son, Allalimya Takanin…

… who bore it a decade and a half later when his people were being driven off their legally-guaranteed and then legally-rescinded reservation and took flight across Buffalo Country to British Territory, where he died at the Bear Paw Battlefield.

Looking Glass’s Memorial and Foxhole at the Bear Paw Battlefield. Photo by Harold Rhenisch.

The alliance was formed, but the Americans neither saw it nor wanted it. Even Clark’s Nimiípuu son, Daytime Smoker…

Pinkham and Evans, Lewis and Clark Among the Nez Perce.

…was involved in the Iroquois effort to reach Clark in Saint Louis in the 1830s and beg him to bring the protection and White power of Catholicism to Salish Country. The Iroquois had in mind the protection of a mission, such as Kahnawake across the river from Montreal, which had protected their outsider status for many, many generations. The Salish and Nimiípuu had in mind the bond of family, and that darned looking glass. A hundred years before, or two hundred, it might have worked, in the style of the Spanish mission culture in the Southwest, but in the new racialized America, it was doomed. Even religion was racial by the 1830s. You can read more of Daytime Smoker and the lost promise of a mixed race culture here. We’ll get to the church’s missed chances soon enough. First, though, look at what unacknowledged childhood slavery did do for the expedition and the history of the United States:

Sacagewea, (1788-1812)

Photo: MPI/Getty Images Source.

Sacagawea, the daughter of a Shoshone chief, was captured in a Hidatsa Sioux raid and sold as a slave to Touissant Charboneau, an Iroquois-Canadien Métis, who made her his wife when she was 12 years old. In November 1804, Charboneau joined the Lewis and Clark expedition as an interpreter. Sacagewea came along, as was the tradition. Her skills proved more valuable. She died in South Dakota in 1812.

What an irony! Thinking they were offering protection to Sacagawea from Charboneau, the American spies actually saw their way across the continent by her cross-cultural status as a slave, proving the worth of Indigenous diplomatic culture over, well, shooting people who got in their way. Sacagewea rescued the Lewis and Clarke Expedition again and again. For this amazing service, Sacagawea has been given a state park at the old Kw’sís village at the estuary of the Snake River in today’s Washington State. There the kids can romp around in an old cottonwood log, and the old ones can have a picnic.

Sacagewea State Park Dug Out Canoe. Photo by Harold Rhenisch.

The broken stones embedded in the concrete are a nice touch.

To continue my recap, generations before, 3,000 children were enslaved in Montreal alone. Most died young as the result of extremely poor treatment. The Foxes, Shoshone, Bannock and others begged to get them back, but although this is how alliances were traditionally made, these diplomatic offers were never accepted by the French, as invaluable as they would have been. The Sioux knew the weaknesses of their French clients well. This loss of potential integration maintained French dependency on trade with the Sioux (as intended) and weakened the economic policies of Louis XIV, who was trying, as kings will, to bring all economic and ritual transactions through allegiances to his person. In other words, the transference of slavery from integration to dominance represented the power structures of New France. And to recap a different theme…

King Louis XIV at age 10 by Henri Testelin (1648)

It’s all in the legs.

King Louis XIV at age 68 by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1701)

Note how he has replaced his fencing leg (age 10) with his ambidexterous other! That’s kingly work, that is.

The kind of not-really-living-in-the-place-you-control is not entirely different today. You can, for example, take a paddlewheeler from Camas, Washington today…

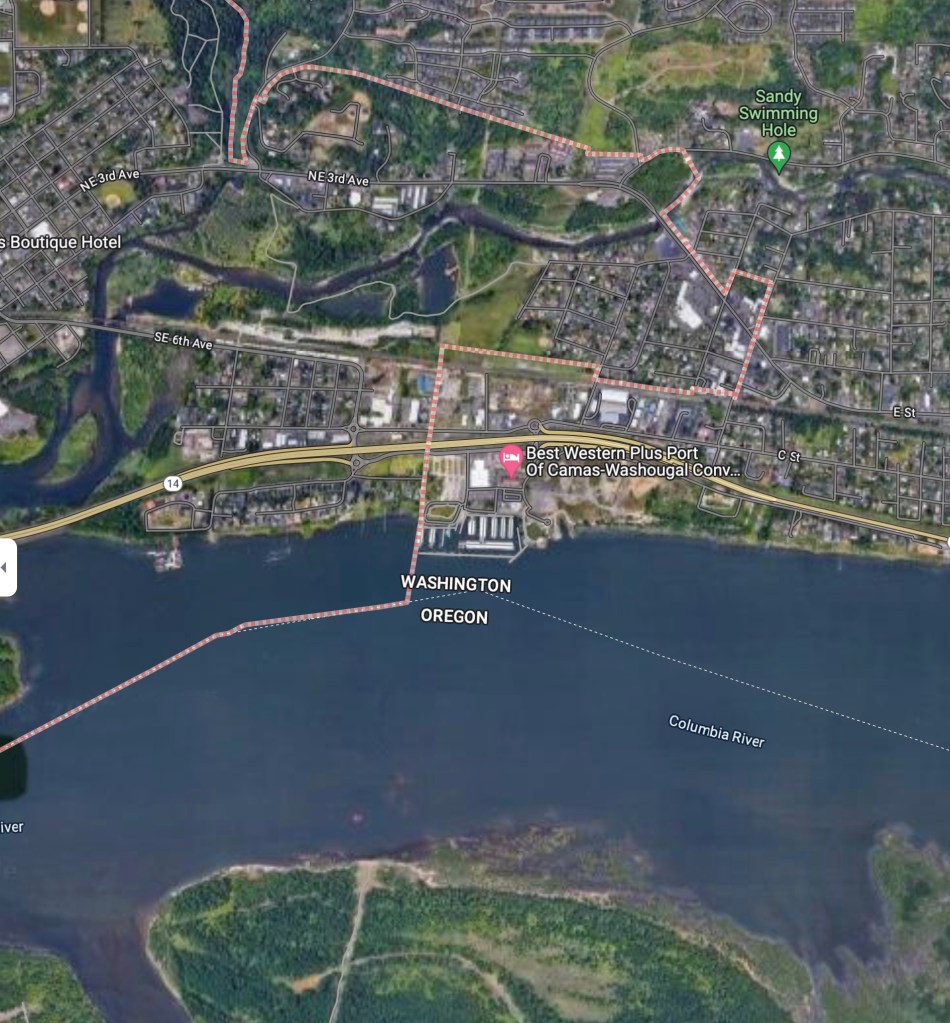

The boat stops at the Port of Camas-Washougall, right below the Best Western There.

It’s such a big boat that if it were back out in the right way from the wharf, the rear passengers would be in Oregon and the front ones in Washington, or vice versa. (Image by Google’s Friendly Bots.)

…on the eastern edge of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s old Fort Vancouver, up through the locks on the Columbia to Kw’sís today…

Something to watch go by while you’re having a picnic. Photo by Harold Rhenisch.

…before heading up the Snake to Clarkston, across from the mouth of the Kooskooskie.

American Cruise Lines Dock, Clarkston, Washington. Photo by Harold Rhenisch

Beats going to Bermuda, maybe.

The rituals of French Power in Louisiana did not represent North American relationships of people and place, either, and were just as much a mythology looking into the distance for a foundation as is an America looking to the South (cleared of the Cherokee) for anchorage in the West, or even just some place without so darned much wind.

Windbreak, Bridgeport, Washington. Photo by Harold Rhenisch

The king’s self-portrayal as the Greek god Apollo, for instance…

The Young Louis XIV as Apollo for the Ballet de la Nuit in 1653. Source.

…a reach into “indigenous” legitimacy by projecting French power and art into the pre-urban roots of European civilization carried weight in France. In North America, where Indigenous cultures were alive everywhere, such statements were about living in the present. The present was not a renaissance through art. Here’s one of the Sioux, dressed just as finely as any French king at a ance.

Sioux Chief W’aa-na-‘taa

No need for Apollo here.

As the Minnesota Historical Society puts the 18th century:

Native people and the French traded, lived together, and often married each other and built families together. Native Americans in the Great Lakes and Mississippi valley regions often incorporated Frenchmen into their societies through marriage and the ritual of the calumet — the ceremonial pipe that brought peace and order to relationships and turned strangers into kinfolk. Source.

That’s the pre-modern world of the West. What followed was a different interpretation. The articles continues with it:

French-Native relations also brought chaos to the region.

Chaos, yet!

The fur trade brought the spread of guns, contagious diseases, and alcohol. French demand for Native slaves resulted in Native people raiding other Indigenous communities. Slavery existed in North America long before Europeans introduced the transatlantic slave trade. Native Americans often took their enemies captive rather than killing them and held them as subordinate people. Sometimes they gave these people as gifts while making alliances, at other times families adopted them in place of deceased relatives. But European colonialism introduced different concepts of slavery, brought new slave peoples to America from Africa, and drove Native-Native slave raiding to unprecedented levels. Slavery was an integral part of the fur trade during this period. Source.

It makes it sound like the solution was to dispel the French and to get American integration in its place, with Indigenous peoples accepted as full citizens. Unfortunately, American fur traders were trading in slaves in California themselves, on a slave-pelt-horse cycle that proved very profitable. Worse yet, while fur traders had taken the place of the Sioux, and amplified the trade to a purely monetary business, without any thought of alliances an the extension of power they could represent, at times the settlers who followed just did the genocide without the slave-taking.

“Protecting The Settlers”, illustration by J. R. Browne in The Indians Of California, 1864. Source.

Between 1846 and 1873, it is estimated that non-Natives killed between 9,492 and 16,094 California Natives. Hundreds to thousands were additionally starved or worked to death. Acts of enslavement, kidnapping, rape, child separation and displacement were widespread. These acts were encouraged, tolerated, and carried out by state authorities and militias.

I will show you more of this when we get down to Sutter’s Fort in California, where the Indian Wars of the west really began. Until then, a little advance view.

New Helvetia (New Switzerland, aka Sutter’s Fort), 1841. Photo from the Sacramento Museum.

A slaving hot spot. To the deaths and enslavements listed above (an below), many thousands more occurred under Spanish administration (and Prussian rule.) Awful as that is.

The 1925 book Handbook of the Indians of California estimated … between 10,000 and 27,000 were also taken as forced labor by settlers. Source.

So, plenty of chaos to go around, really. Integration, and the union with the land of which it spoke, was not in the cards. Enslavement of the land (and the treating of its people like beavers) was.

Orchards, Hayfields and Pastures Not Fitting In. Photo by Harold Rhenisch.

Looking across the Columbia at alienated lands on the Colville Reservation. Photo by Harold Rhenisch.

The Sioux and Iroquois were not operating by intellectual or indigenous traditions from Greece or France, the cultures of which had long been subordinating people to central authorities and transforming land-based peoples into a proletariat in a market economy. The irony in that is that the newly-arriving promoters of liberty were, in a tradition that had done so to the Scots in the Highlands. Such struggles were why the Scots were in North America in the first place, imported as native warriors from outside civilization. It’s also why they often joined up with the Cherokee. In North America, they were nobody, that’s to say that in European culture they were subordinated as a proletariat, the landless working poor, and that is another form of slavery.

Photo by Harold Rhenisch

And it includes the beavers.

Next, I will draw the connections between Métis culture in the Red River and the American fur trade, to emphasize just how profoundly Indigenous all this history was, as Indigenous people struggled to maintain independence through cultural change, with no desire to be branded as a people of the past. See you then.

Categories: First Peoples, history, Pacific Northwest