100 Sustainable Paths for the Okanagan: 19

Currently, agriculture in the Okanagan Valley is industrial, in keeping with colonial models from 1858, when water was diverted through Nlaka’pamux villages in the Fraser River Canyon to flush out gold in the gravels beneath them. This Okanagan mother and her twins do not live within that industrial form.

It is exciting to see Indigenous peoples in the valley and across the entire industrialized landscape known as Canada call for an end to colonialism, and exciting to be among the voices asking for it to end soon. More, however, needs to be done. It is simply not enough to stand within the benefits of industrialized water and complain about colonialism as some distant force, perhaps deep in the past, perhaps expressed through systematic racism (the privileging of people of one race over those of another by inherent biases built into political and social systems lived in by otherwise well-meaning people), perhaps in addressing the inadequate responses of police forces and courts to the murder of far too many indigenous women or the incarceration of far too many indigenous men. Bound with industrialized water is also industrialized land. I know I have pointed this out before, but I think I have found a way to make a clear point about it. I hope you will follow along for a moment. This is important. If you feel you can’t follow along, here’s an image to leave you with.

Crab Spider in the Asparagus (Camouflaged as the Sky)

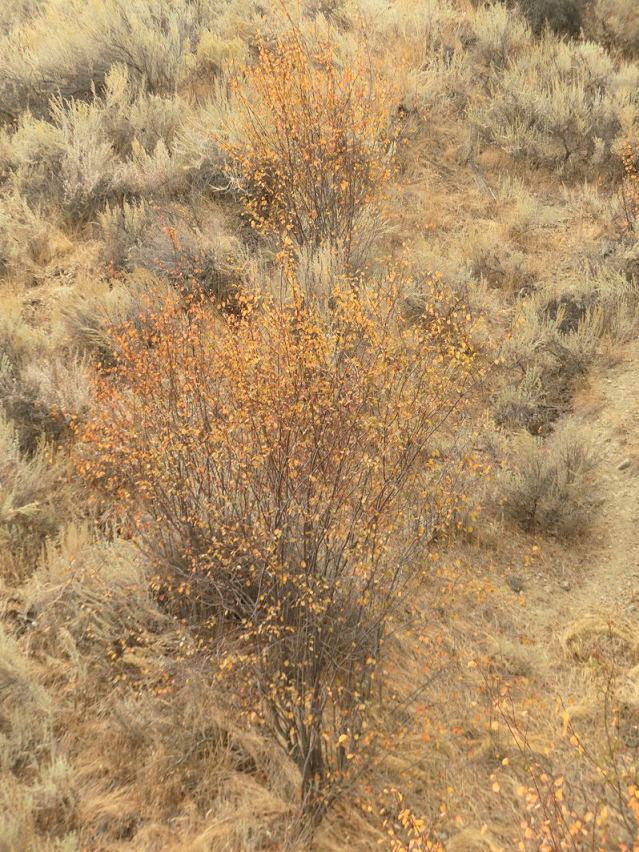

If you would like to follow along, here is another image of wild asparagus, a few weeks later. This one has gone yellow, after a long season of ripening.

What I’d like to draw your eye to here, other than the asparagus, and the ability of your mind to instantly pick it out of the background slope — your mind is evolutionarily selected to do that —is the hill in behind. In the industrialized space called Canada, this is what is simultaneously called “wild nature,” “private land” and “a farm.” What it is farming is a few cattle, which eat the “nature” off of the space. That is a pure image of colonial activity. This “nature” actually consists of large swathes of overgrown sage brush (the consequence of overgrazing by those cattle) and cheatgrass, an invasive and destructive weed from the Russian Steppes. In the colonial, industrialized space, these two species, which have replaced hundreds, are called “wild,” although they are almost completely domesticated, in keeping with the industrial nature of this space. Note that the asparagus plant, which is not native to this place, and which is also called “wild” is not part of the industrial project. Here’s another.

And another. This one is reclaiming a seasonal watercourse created by erosion from industrial activity to lay a natural gas pipeline nearby. Notice the lack of water in all of these images.

The erosion here is not just geological. It is cultural as well.

For reference, the images were made just to the middle left of the image below. Notice that here water is flowing down in a dry channel between the pressure gradients of the hills. It doesn’t show on the surface as liquid water, familiar from industrial systems, or cropped water, familiar from orchards, grain, hay and vegetable fields using industrialized water, but as a system that passes water along from plant to plant to plant. The plants are the water system, not its recipients.

In that spirit, have a look again at Asparagus, but this time closer up. She is being fruitful.

In that spirit, have a look again at Asparagus, but this time closer up. She is being fruitful.

She is also wild water. Did you catch the significance of that? I hope so! It’s worth spelling out again, because it’s such a powerful example of the post-colonial future we need to form on this land. Asparagus is a newcomer to this land, but lives on it without support, is fully integrated into it, not only lives without free water but enriches the land for many species, including humans, leads people into their natural habitat, opening other opportunities to them, and can be planted and gathered without capitalization. In short, we don’t need provincial parks, preserving wilderness — another colonial idea — except from ourselves; instead, we need more asparagus.

In the process of deindustrialization, it is important that ancient relationships with the land be maintained, such as the relationship between the syilx and their horses. This is a relationship that goes back a long way in time, possibly far longer than the 1790 proposed by non-indigenous scholars. At any rate, whether 220, 500, 1000 or 20,000 years in the past, the gift of horses from the land to the people was accepted.

In the process of deindustrialization, it is important that ancient relationships with the land be maintained, such as the relationship between the syilx and their horses. This is a relationship that goes back a long way in time, possibly far longer than the 1790 proposed by non-indigenous scholars. At any rate, whether 220, 500, 1000 or 20,000 years in the past, the gift of horses from the land to the people was accepted.

The Horses of the Okanagan Indian Band on the Communal Reserve Pasture in April

The Horses of the Okanagan Indian Band on the Communal Reserve Pasture in April

Asparagus is making the same gesture today. There are complaints that horses gouge up and erode the grasslands (true), and suggestions that they be killed off to free up the range for more cattle or just more grass, but that’s offensive. The problem is not the horses but the number of horses maintained on constrained space created by industrial water and industrial land use. Private land, whether it is land set aside communally on an Indian Reserve or land privatized for the benefit of a single individual, is a sister of industrialized water. Land usage rights were also set in 1858 in British Columbia, and rose out of Gold Rush era water law and its structural racism. If there were enough land for the horses, there would not be an issue, and, besides, if horses are unacceptable as “non-native”, then so are cattle, and the industrialization of the land that makes space for them out of what were richly producing fields of plant crops 170 years ago.

What’s more, Asparagus has a cousin, with wings, the ring-necked pheasant, which has adapted to this land as well, and often springs up underfoot in an explosion of wings, leading to photographs of departures, such as the one below…

… or the one below…

Like Asparagus, they pay very little attention to private property rights, which is to say they pay very little attention to colonial issues or issues of cultural appropriation, because they have appropriated nothing. They have gone wild. Asparagus has as well. Here is some in the spring. She uses a fence line, a boundary space where she can express the tendency of water to find the sun. She becomes the vertical green river that expresses that force.

She can even compete against cheatgrass:

Food for deer (and humans), Asparagus nonetheless puts out enough shoots over a long enough period, that she outwits the seasonal patterns of deer and humans.

There’s a lot of pressure on Asparagus, yet she manages, and she has a lot of seed. Birds get some in the winter (and they sorely need it, as neither cheatgrass nor sagebrush are adequate replacements for the seeds of thistles, wild sunflowers, waterleaf and lilies, to name a few.), but there is still more.

Beautiful, too. In all this work, Asparagus has fit in nicely to the work of Saskatoon …

… thistle, chokecherry, hawthorn, wild plum and dogwood on the “dry” hills and spearmint along the water and provides the foundation for cultural renewal, not cultural removal. Look at her again, healing the wound of a human mistake.

Look at the slopes.

Such slopes stretch for ten kilometres high above the city. Much of it would support gardens of asparagus, sunflowers and Saskatoon berries. All of them would draw people out on the land for recreation, while picking them.

Future Asparagus Farm

The sunflowers would support birds and the starving deer. The saskatoons would support yet more birds, and the starving deer. And the asparagus…

Note the Lack of Pests. Thanks, Birds.

… ah the asparagus…

Dinner for Four

…sells for $6 a pound in the supermarket right now, grown on nitrogen fertilizer and flown in from South America while we delude ourselves that we are a post-colonial society that needs to make living conditions better on Indian Reserves. We need to get rid of reserves, not to assimilate native peoples into dominant colonial culture, but the other way around. The land will have the last say on this.

Future Orchard, Coyote Highway, Asparagus Field and Recreational Area

Over an acre of land, at a density of one asparagus plant per 100 square feet, sheltered initially in young hawthorns or old sage until being cut free, we could foresee 420 asparagus plants per acre, or perhaps 200 pounds of asparagus. Over 10,000 acres, that would be 2,000,000 pounds of asparagus, or 1,000 tons. The land is not making that much off of cattle, which means that its industrialization, its privatization into the hands of industrial men for the creation of an economy and the support of communities and their infrastructure, has been a total failure. Moving forward into a post-colonial model would make us all wealthy in this valley. Failure to do so will ensure the continued acceleration of industrialization and industrial development, and the steady furthering poverty of the people and creatures of this place. That’s how structural racism works. Water is part of that story. We need land and water reform.

Categories: Arts, Endangered species, Ethics, food culture, Gaia, Grasslands, green technology, Industry, invasive species, Land, Nature Photography, Spirit, Water

An impossible question, I suspect, but is wild asparagus similar to that which is commercially grown. I live in a part of England that grows a lot of commercially grown asparagus. I try to support local businesses where possible that are not controlled by impersonal commercial organisations, where the farmer also contributes to the strengthening of the local community.

LikeLike

It is the same asparagus! It just climbed over the fence. What’s more, the industrial farms on which it was grown have long since ceased to grow it, but up on the hill the escapees thrive. The numbers aren’t high, but that’s because of the chance involved. A bit of human attention could do amazing things. Very true about your local farmers. I try to do the same here. If I run out of anything from my own garden. I hope to get up a post about industrial food and its high costs. Let’s hope I find the time today!

>

LikeLike