The above image shows what lives here: ponderosa pine, a thick ground cover of lichens and mosses, saskatoon bushes, giant rye grass, bluebunch wheatgrass, hawthorns, chokecherries, and mule deer. That works well. This doesn’t work:

The above image shows what lives here: ponderosa pine, a thick ground cover of lichens and mosses, saskatoon bushes, giant rye grass, bluebunch wheatgrass, hawthorns, chokecherries, and mule deer. That works well. This doesn’t work:

These animals screw things up. These ones too:

It might be pretty, but it’s a nine species ecosystem: (red and purple) cheatgrass, big sage, mustard, and horses. There are likely grasshoppers, a mess of sagebrush sparrows hanging around too, a meadowlark or two, a bunch of voles, and a hawk. Land like this once looked like this (1000 species):

And even that remaining grassland on the Chilcotin River is not precisely pristine, as the deep erosion of the streambed in it is the result of trapping all the beavers to make hairpieces like this:

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (r), with Sir Winston Churchill (l), ca. 1939. — Image by © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

Grassland like that attracted cattlemen from Oregon. Within two decades, it looked like this:

There’s a word for that: inedible. When the cattlemen came through, it was rich and productive land, capable of supporting a large number of animals. In fact, British Columbia was built on the stomachs of those cattle. This is what was lost:

As you can see, it has a lot of cellulose but not a lot of green. It’s also on hillsides, and what do cattle do on hillsides? Why this:

This too:

(Note the 100% lack of bunchgrass, which is capable of surviving the summer heat and modulating the flow of water down the slope) Worse yet, cattle do this:

They are tramplers, that’s what they are. Not only does this water have no more ability to hold water, but it has no ability to support any animals except, um, god, I don’t know. Beetles maybe?

So it goes. Land which was once valuable and rich …

… becomes valueless by ignorance, and rich grazing land …

… becomes a sand pile lightly cloaked with weeds that shrivel up in summer…

… and quickly become capable of supporting nothing.

A cow could get the nourishment of the slope below, with its lost mosses and struggling, thinned-out bunchgrass …

… or of this one …

… or this one …

… out of a couple handfuls of weeds pulled out of the ditch, where the water flows. That’s why horses are always leaning over the fence, by the way. They’re hoping for mercy. So if anyone tells you, ever, that the Okanagan is a dry, parched land …

Not parched! Those stalks are just there to catch the rain.

… please tell them of the culprits. This:

That’s how much land one cow needs now!

and this:

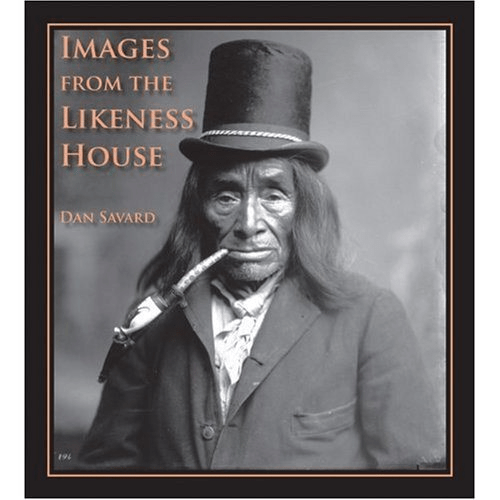

Unidentified Chief in the B.C. Interior, c. 1897, possibly mis-dated and Chief Nkwala (This bunchgrass was his).

Note the cylindrical beaver on his head for which his people traded their water in a gamble for survival, only to lose the land.

Here’s some bunchgrass doing well.

Here’s some cow hell:

And that’s the good part. The land below is even more of a desert.

Private property rights should not be allowed to negate the power of the land, so that the land can be disconnected from life and then sold as a commodity. That way lies poverty and the entrapment of people into communication chains powered by petroleum and distant political forces against which one is powerless to effectively act.

Private property was meant to give freedom. It has become, in this land, a tool by which to deny it to ourselves while denying life to the earth. This is not an insolvable problem. The solution is simple. First, get the cows off the grass. Second, get the horses off the grass. Third, tie land ownership to land stewardship instead of to non-organic “improvements”, which is a word for “estrangement from life.” It can be done. It has been done. The land below was grazed down to cheatgrass 140 years ago.

Junction Sheep Range, Chilcotin River

This is what its slope looks like now.

This is a planted bunchgrass slope in Vernon, in the Okanagan:

This slope gets about 2 centimetres of water a month, including up to 60 centimetres of snow. None of it flows away. Not a drop. The grassland below is grazed for two weeks a year and walked on for many more:

Hikers Returning from the Farwell Dune, Chilcotin River Canyon

It can sustain that, forever. Two weeks, by the way, supports a far heavier cattle population than this:

It’s not dreaming. It’s simple dollars and sense. What stands in the way? What it always was: bad land use policy. Remember we began here:

Nothing begins here:

Except hunger.

Categories: Agriculture, Erosion, Ethics, First Peoples, Gaia, Grasslands, invasive species, Land Development, Nature Photography, Urban Okanagan, weeds

Environmental restoration focusing on sustainable ecosystems is the key.

LikeLike

Yes, our job is to enable sustainable environments to flourish, to strengthen them, and to live off of the extra energy of the land, which is a reflection of the energy we have put in. All farming has done has been to graze down 10,000 years of indigenous energy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You say it so well.

LikeLike