Business has always been a primary foundation of the development of the West of North America, with diplomacy being subordinated to it. The development of Cascadia is no exception. It was an active distinction 200 years ago and it is an active force even now.

A Car Wash Business in Chelan, Washington. Photo by Harold Rhenisch.

Presumably of use after you have destroyed the grassland and set it up for castastrophic erosion by running your vehicle straight up a hill. What could be more perfect?

This includes French business. Cascadia was never part of New France, but much of the West was. And it was business. Before Louis XIV subordinated New France directly to his power in 1663, New France was operated by The Company of New France, a chartered mercantile company (the Hudson’s Bay Company that controlled the North was a British equivalent), tasked with providing income to the crown and settling the colony. The goals proved contradictory and impossible for a group of merchants. Here, however, is their headquarters in Quebec City today.

Have the Moules Frites

Just a friendly tip.

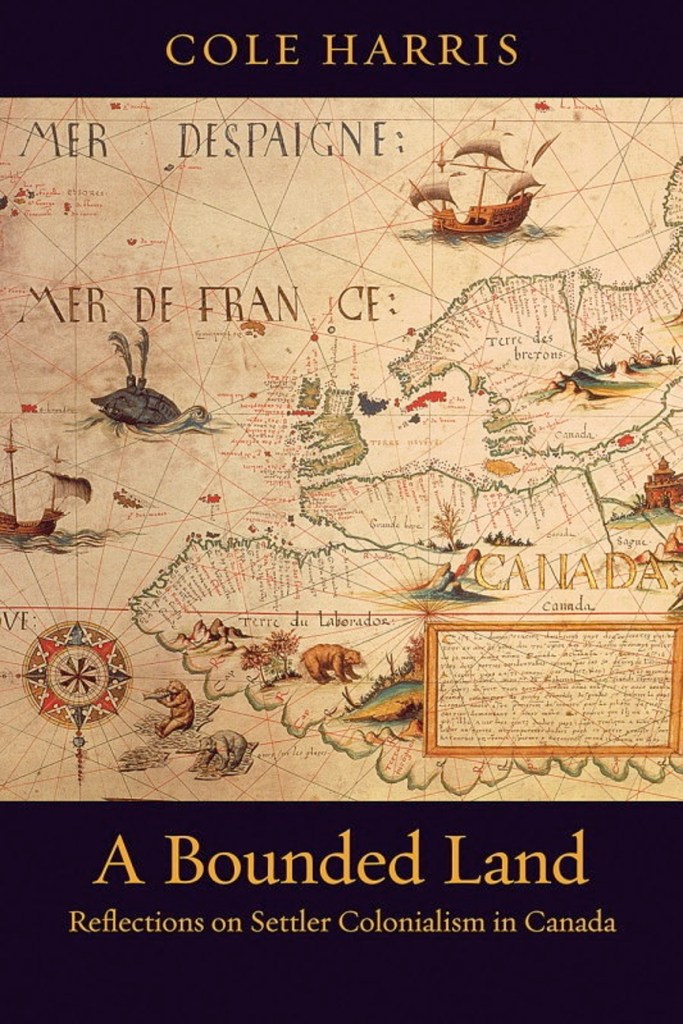

As trapping for the company was done largely by the Haudonosaunee (Iroquois), few French men were needed, business-wise. Populations were slight: 3200 French in 1663. Because of their low numbers, the French were susceptible to Haudonosaunee attack, which was not good for settlement or business. To counter this very real threat, Louis began a program of settlement. The population rose to 6700 by 1672. That’s more than double, yet it didn’t lead to much increased density because the men of New France expanded across the continent and down to the Gulf of Mexico instead, meaning that the St. Lawrence Region (Canada) remained underdeveloped and colonizers were still spread thinly. Established ways of independence in the forest stuck, as the geographer Cole Harris explains in his detailed history A Bounded Land: Reflections on Settler Colonialism in Canada:

Harris’s study of Quebec reveals the poverty of agricultural settlement in a region almost totally unsuited to agriculture, weakened further by the habit of Quebeçois men to slip away after harvest, illegally trap furs against the government’s monopoly charters, and slip back in from the forest for spring planting. Everyone’s farm butted up against the forest in back and with little care given to the land the farms were in the main subsistence enterprises (as they largely remained well into the 20th century). Local aristocrats, tasked with living off the proceeds of these lacklustre enterprises tended to stay in Montreal instead, as the proceeds were few, install priests, in order to try to get some hierarchal order into things, or tax their landholders extravagantly, which, of course, pushed more of them away from the farms. That was an easy form of resistance.

Running a settler economy when people don’t particularly want to settle is tough. The sentiment applied to Indigenous people, who did not want to be settled upon, and to the French, who didn’t really want to settle.

Mind you, there was a whole human social world out there, and bountiful rivers and plains and forests, so why not.

The dearth of farmland along the St. Lawrence. Many of the areas marked “nil” were actually farmed, to no good end. From A Bounded Land: Reflections on Settler Colonialism in Canada:

The furs trapped out in the bush were laundered on a black market. This whole ad hoc system of workarounds and extraordinary relationships was all soon reflected in the Sioux’s manipulations far to the West, as the Sioux tried to contain the French expansion did. In the end, France’s ceremonial notion of centralized government and his regime’s failure to appropriately integrate with the land’s people led to the land and its people working for his officials or against then, but rarely with them. That would have been decentralization. The image below displays a similar instance of non-integration at work in Cascadia today, not in French but in American culture:

Workers’ Memorial, Grand Coulee Dam, photo by Harold Rhenisch.

A path out of the Depression for workers from the American South and East was Apocalypse for Cascadian salmon peoples, such as the Sinixt, the Skoelpi, the Spokanes, the Sanpoil, the Ktunaxa and the Kalispel.

The 18th century also saw the formation of Assiniboia, another attempt to mediate between British, American and Indigenous cultures by maintaining an aristocracy on the shoulders of a subservient and compliant peasantry (the Scots). Unfortunately for the scheme, many of its players considered themselves independent instead. And that was trouble. (For details on Assiniboia and its connections to Cascadia, please go here and here and here and here.) To sum up, Assiniboia was created to use the tribal loyalties of Highland Scots to block the northward migration of American settlers, just as the Scots themselves had previously blocked the northward aspirations of England. It was like having an army without expense. It also interfered with Métis and French-Canadian aspirations, as an example of how mercantilism doesn’t make for effective foreign policy. Again, the issue continues today.

Vietnamese protesters shout slogans in front of the Chinese embassy during a rally in Hanoi, May 11, 2014. Source.

Here’s a point that the American historian Joseph Gaston…

Joseph Gaston: Railroadman, Republican Newspaperman and Rancher. He was also a French protestant, driven out by a Catholic regime, in other words a direct enemy to the Oblate priests who would show up 20 years later. Source.

…described fairly accurately:

The point is well-made, although a bit over-dramatically. The king was checked: by parliament, which, in the end, gave Gaston’s Oregon the HBC lands. Still, Gaston’s hyperbole…

… is stirring stuff. Nonetheless, its argument is weakened by the shooting at Pierre’s Hole and threats to Ogden in 1826 by an American, Gardner, that he would join with the Salish and the Kutenaxa to drive the HBC out of the Pacific Northwest, without recourse to any court or legislature. Gaston’s interpretation, however, became history, which he presented in his The Centennial History of Oregon, 1811-1912, even though it was only another salvo in a long-running proxy war. Which continues. At Moses Lake, perhaps, a storage lake for water diverted from the Columbia to water millions of acres in the Columbia Basin..

Moses Lake, Washington. Photograph by Harold Rhenisch.

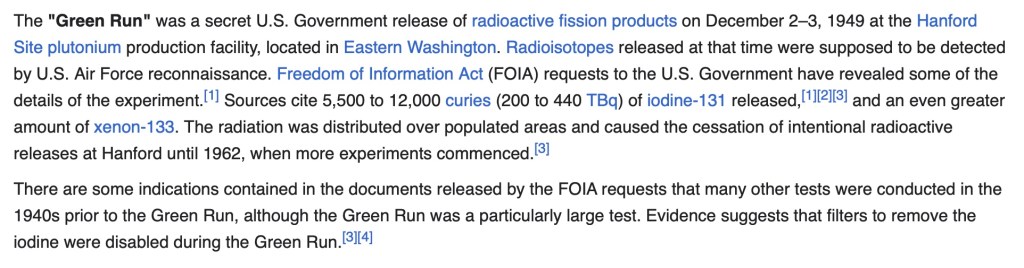

..which was secretely radioactively poisoned from the Hanford Nuclear Reservation to the west in 1949, in a test to measure atmospheric radioactivity so the US Air Force could calculate from it how much plutonium the Soviet Union was producing in the Urals, so it could know how many atomic warheads the Soviets had.

So, yeah, a proxy war in many ways. Here’s another, subtler one:

Lone Pine Replacement Fishery, The Dalles, Oregon. Photo by Harold Rhenisch

According to the terms of the 1855 Walla Walla Treaty, the Nimiípuu, Umatilla, Warm Springs and Yakama Nations that signed the treaty were accorded

the exclusive right of taking fish in the streams running through and bordering said reservation is hereby secured to said Indians, and at all other usual and accustomed stations in common with citizens of the United States, and of erecting suitable buildings for curing the same. Source.

Building a dam in the river, which drowned the accustomed stations has proven costly to the US Government.

Lone Pine In Lieu Fishing Site, The Dalles, Oregon. Photo by Harold Rhenisch

It has also led to a contrast in cultural expression, between modern and pre-modern, on racial lines.

Photo by Harold Rhenisch.

And has now lead to resistance to salmon protection, to guarantee the treaty rights that were a condition of US ownership of Indigenous lands. In other words, wouldn’t the land legally revert to Native rule, if the treaties were no longer honoured. Obviously not, but the mechanism of absorption is troubling. For one, here’s a report on the findings of a study at the University of Oregon:

Hatcheries, a high-tech fix, seemed like a political answer to a lot of land hunger and a lot of agricultural resistance. Here’s an article about how legislation to help the salmon, in order to meet the terms of the treaty, are getting nowhere in the Washington Legislature:

Tellingly, these government-to-government crisis is set forward as an environmental story:

The Haudenosaunee knew well these techniques of transfer of power using the law as a lever and defense against the law. This great people, who had sided with the British in the War of 1812 in order to protect their homelands in the Northwest, lost everything to a cleverly worded treaty that promised much and delivered nothing.

The Old Northwest in 1792. The Haudenosaunee Empire filled much of this region.

After they saved British North America by allying with the British against the Americans during the American Revolutionary War, the British gave the southern portion of these lands to the Americans in 1779. After they saved British North America by allying with the British against the Americans during the War of 1812, the British gave the northern portion of these lands to the Americans in the 1814 Treaty of Ghent. Suddenly the Haudenosaunee were homeless.

It’s no wonder Iroquois and Haudenosaunee men went to the far western portion of the Northwest with The Northwest Company and its American competitors, both immediately before the war and immediately after the treaty. It was a proxy war of its own, fighting the war by mercantile means as a way of saving an old, unbounded lifestyle. The contradictions were too much to hold for long. It is, however, no wonder that Iroquois feelings towards the British of the HBC were mixed at best, or why they didn’t just simply go to the Americans. They didn’t trust either group, and for historical reasons. The Iroquois were forced by the grey territory between trade and diplomacy to remain independent actors, choosing allegiances to suit their circumstances, only now without an empire or much beyond individual power. In other words, they were deeply modern men.

Old Ignace. He came with David Thompson of the Northwest Company in 1809 — to lands his people had traded in for generations. He is here as a Flathead chief through marriage. Source: Jean Barman, Iroquoi in the West. Source.

Even in 1797, the Haudenosaunee plight had been desperate. As Colin G. Calloway puts it in his book White People, Indians, and Highlanders: Tribal Peoples and Colonial Encounters in Scotland and America:

A Fascinating Set of Parallels and Intersections

First, 1779…

It might be a mistake to read these people as completely miserable. An important Indigenous principle is that the land provides, meaning that those who control the land have a duty to pass on what it provides. The principle was continually misunderstood in the Pacific Northwest a generation (or even three generations) later. Care is warranted not to misunderstand it here, either. This is not a defeated people. They are, however, hungry. They would be defeated soon, however, although Maclean’s anger is oddly one-sided.

He might have swept up the British in his rage as well, but… well, let’s ask.

Interview with a Ghost, June 28, 2023. Transcribed by Harold Rhenisch

The Empire was overextended. As Calloway notes:

Note Maclean’s conclusion:

You might think I could line up a book squarely in a scanner, but (sigh) no.

Calloway’s own conclusions, are, perhaps a little more one-sided. Strictly focused on his (admirable) thesis about Highlanders being treated as wild, tribal, Indigenous people, he notes:

Sigh.

He could as well have talked about the dual stresses of the Haudenosaunee in the Rockies (and then at Pierre’s Hole.) Oh, but wait, an interruption!

The Teton Range Source

Interview with the Teton Range, June 28, 2023. Recorded by Harold Rhenisch

Next: the Iroquois response to this squeeze. See you at the Rendezvous.

Categories: Ethics, First Peoples, Pacific Northwest