Can we map land and water like this?

If we reversed it, it would be a different map, like this:

This profound difference would, I think, be honest. It would reflect how human minds observe the world. Working with that consciously would give us considerable power. It’s not even a stretch. Words have the ability to work like this. For instance, this …![]()

… is quite a different map to the landscape than this…

… although the image are identical. This ability of words to colour their surroundings is something poets know very well. For example …

I learned to write poetry by pruning fruit trees. It is a form of sculpture that shapes light and air. The scree slopes above me were so high and steep they were the sky. Mountain goats tracked across them in white lines, always with the young in the centre of the herd. A kilometre below them, bees settled on the wind-tossed blossoms of apple and pear branches rooted in gravel. I moved among them. Wind tugged at my shirt. In the spring, a clatter of rocks dislodged by the goats often cracked across the valley air and lifted my head.

… is quite different than this:

I learned science by pruning fruit trees. It is a technology that shapes light and air. The scree slopes above me were so high and steep they looked like the sky. Mountain goats tracked across them in white lines, always with the young in the centre of the herd. A kilometre below them, bees settled on the wind-tossed blossoms of apple and pear branches rooted in gravel. I moved among them. Wind tugged at my shirt. In the spring, a clatter of rocks dislodged by the goats often cracked across the valley air. I paused in my technical education and lifted my head to watch them, then got back to work.

Generally, this difference is called meaning. Poets know it isn’t. They know that meaning is an illusion and that the components that make it can be interchanged, or transformed by differing context, such as the difference between this vole track…

and this one…

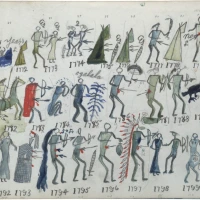

Both bridge gaps between shelter by burrowing under the snow (which then melts away in the sun, revealing these dashes through semi-exposed space), but the exposure and danger is quite different in each case — enough so that many languages would have different words, or at least ones inflected very differently, for them. English chooses, instead, to colour with context. In keeping with the four-part organization I showed you earlier, here’s an example of that principle at work when freed from meaning:

The Icelandic sculptor Ásmundar Sveinsson called effects like this sculpture for the eye, to give it delight as it sorted light and form before sending information on to the brain for further massaging. A trip to Reykjavik is just a pub crawl if you don’t get to the Ásmundarsafn, the gallery set up to show his stunning work.

It was a concept that has not yet seen its day.

These weren’t intellectual interpretations of human forms, human work and human engineering. These were delights made for the eye.

(You can view this, and more, work by Ásmundar on my Icelandic blog, A Farm in Iceland.)

Note that the quality of the light is part of the effect that he was sculpting. And, yes, he was doing more than playing. He was making interfaces between human bodies and the world. Maps, in other words. Here’s another example, again following the motif of the four quadrants of a compass…

This one is a map of a transformation, or fields of energy. So, what I have in mind is working directly with the mind’s organizational principles, the right brain that sees emotional, holistic and intuitive material and some rational material, the left brain that sees rational ordering plus some emotional, holistic and intuitive material, coupled with the pre-sorting of the eye, which Ásmundar was exploring, to create a world deeply written with pattern, such as these brown-eyed susans…

You might like to read my post The Language of Flowers, to look into other human readings of these mysteries.

…to make accurate maps of attributional effects. We can start like this, with a compass but also a left-right and up-down ordering.

It is, in effect, a map of the human body, with its horizontal and vertical axes. Here’s how Leonardo saw that:

Here’s some play with it.

I made that map at the old cloister at Skriðuklaustur, Iceland, on a cold, late-winter night after visiting Reyðarfjörður (Whale Fjord) in Iceland in a brief break in the weather.

(You can read about the visit, here: https://afarminiceland.com/2013/04/30/the-view-from-canada/ and here https://afarminiceland.com/2013/03/12/gunnars-warning-to-the-germans/)

Still, we can apply it to the Okanagan.

In this conception, the directions have cognitive significance. In other words…

But look, our emotion and order can take the opposing forms:

They can even change roles!

The content is not really the story!

However, as poetry teaches, shifts in perspective can be within as much as without. The following game, for example, is nothing without the equal sign. It acts as a title; it colours all the material to the left and the right.

It’s at the centre. How does all that look in the world? Well, maybe like this, with Leonardo’s circle of human reach.

After all, circles are spaces of equality, more than lines are. However, that circle is empty and the world is not empty. If you find yourself empty in the world, the Earth will soon fill you. In that spirit, here’s a female coyote watching me 150 metres above this estuary. They are two sides of the same landscape, despite their apparent difference.

And here this joined landscape is again, with our quadratic grid. Each quadrant carries a different weight and balance of emotional/ordering information.

We can even give them compass directions, knowing that those, too, carry cognitive and perceptual weight.

Look, however, how the lines slide through the four quadrants, not a part of them at all, and serving only to cast light on them. That’s truly beautiful. Is this enough to be a map of the land? In a way it is. It provides all the information a poem would provide. The coyote, for example, is near the centre of the image, in the emotional quadrant but near the mirroring east-west line, and thus a trick of the eye (In fact, she looked like a stump until I brought the camera to my eye and zoomed in), and barely over the line from the rational field. As a result, the empty bunchgrass and sagebrush to her right is loaded with her presence, while the quadrant above her is loaded with her height, or her vanishing into thought, while the NE quadrant brings the emotional component of rationality forward). We would expect her to leave in that direction. In fact, her mate is in that quadrant, just below the middle of the EW line. She is just about to join him here, before they climb the hill just on the west side of the NS line, right where emotionally and rationally we would expect them to go.) Our consciousnesses and bodies and those of the coyotes are locked in this moment. I believe these correspondences make this is a map. Providing a human with a map like this would indicate where the flow of the land was, where the flow of coyotes across the land was, and so on. What more does a map of place need? They are all tracks to follow, processed long before consciousness even is aware of them, no different than the tracks below.

Humans, coyotes, deer, everybody is going towards Terrace Mountain, glad to be away from the sagebrush jungle for a moment.

It’s just that they include non-human actors and require a strong dose of holistic thinking in order to be read, but there’s the thing: we are all 50% holistic. We know how to follow these tracks. In that, we are not alone.

In a prose-based culture, this needs to be said. If this were a poetry-based culture, these correspondences would be dominant.

Categories: Arts, cartography, Ethics, First Peoples, Grasslands, Industry, Nature Photography, Spirit, Water

Thank you, it was amazing post again, Love, nia

LikeLike

I’m glad you liked watching me walk way out on a limb, and that you were there underneath in case I fell off. 😉

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent post.

LikeLike