Technical wine-making is a new invention. Before that, wine-making was an art. It still is. That’s what I’d like to talk about today, because discussions of winemaking usually give short shrift to its Catholic roots, and that’s too bad. There’s much knowledge there.

Vineyard Shrine in the Rhine Valley

Looking a little forlorn, yet not quite forgotten. The narrow footpath in front of this cross was the main north-south route from Switzerland to Hamburg, for anyone not making the journey by ship. These vineyards were quite badly bombed by US Air Force raids on Frankfurt am Main in the Second World War, a target the US navigators missed by some 20 kilometres.

Here’s a closeup of the prayer at the base of that cross:

Welcome to the Kingdom of Heaven.

Rough translation: “The noble wine that thrives here heralds God’s Grace and the Glory of his Kingdom.” In other words, these grapes are like the angel Gabriel.

Wine technicians have trouble with the notion that wine and the land share a spirit, so they break it down into specifics of soil, drainage, slope, sun, and vineyard practices. In so doing, they provide an invaluable service. We need these guys. What they miss, however, is the social aspect of the wine. It’s the effect that will cause a person to spend $20 for a BC red, such as a 2008 Robin Ridge Merlot, instead of $10 for a superior Malbec from Argentina. Neither is a great wine, but one’s better than the other and it costs half as much. That $10 translates into affection for place. I wouldn’t scoff at that. That effect used to be a part of the wine’s terroir, or its earth. Here, for instance, is a bit of terroir from the southern tip of the Rhine Valley at Rüdesheim. This is the northern point of the home soils of the great white grape, Johannisberg Riesling, which originated on the heights about eight kilometres south of this bend of the river, some 1100 years ago.

November on the Rhine

Notice that unlike the vines of the Okanagan, in this region vines keep their leaves deep into a long, damp fall. The result can be wines that have fully finished the photosynthetic processes of transforming their leafy acids into sugars. In the Okanagan, the way to mimic that is to create ice wine, which mechanically concentrate sugars. At its worst, this is a process otherwise described here.

Not all vineyards along the Rhine are still farmed. Many hand-farmed plots have simply been let go. They include a secret as to what all modern technical discussions of terroir miss:

Abandoned Vineyard in the Rhine Valley (Across from Bingen)

Such farms are found on small, steep or shady plots all up the Rhine Valley. The rail line and the highway separate them from the river now, but that’s a relatively new thing. The concrete retaining walls for both transport systems still contain steps by which a man could haul water up to his vines, and his produce back down for transport — all by hand. The microclimates produced by the heat retained by all this rock, ought to have produced some pretty unique vintages, just as the isolation produced interesting characters.

Simply put, a man’s relationship to the land, and the relationship of other men to him, is part of how men used to read wine, and the land through it. It was pretty poetic stuff, yes, but not foolish. Nonetheless, here’s what missing that human connection sounds like, in the mouth of a technical wine writer:

“An experienced taster is familiar with the distinct characteristics of wines from a particular region….These characteristics can be reliably identified, and are described by the vignerons and wine writers as being ‘gout de terroir’. However, the big problem with this position is that included in this definition of terroir are the traditional winemaking procedures, which in all likelihood are crucial in imparting the local character to the wine. If winemaking practices are to be included in a definition of terroir, this stretches the concept so far that it is no longer of much use.”

I feel for this guy. He’s trying to separate the taste of the land in the wine from the land itself, by pleading for logic. Good luck. The logical discipline that would lead to such control over human taste and perception is not exactly a dominant human characteristic. Even the physical work of caring for the vineyards has not always been seen as a set of physical tasks. Take Rüdesheim, for instance:

Rüdesheim am Rhein

On the steep slopes above devout, Catholic Rüdesheim, vineyards rise up to the heights of the Niederwald Forest.

To care for the Riesling and Grauburgunder grapes of Rüdesheim, men carried everything for the vineyard on their backs, and carried the grapes back down in large wooden cradles. Then they turned around and carried manure and night soil and marc right back up. The spiritual symbolism of all this went as follows: men lived in a village on the river, clustered around their church, in which they honoured God. The most devout form of their prayer was the cultivation of the vines, and the honouring of the spirit of God that soaked into them through the sun striking them on the slopes. It looked a bit like this, up there:

The Kingdom of Heaven

All a man has to do in this life is bring the solar energy of the vines down into the dark cellars of winter and ferment it to make it live on and animate men and women throughout the years to come. It was a brutal, physical penance, but the rewards were the ability, just in an instance, to touch (or taste, really) God. He filled you, not only with His presence, but with the whole year, and the land itself, distilled by the vines and human attention, into wine. Wine-making and grape growing were prayer, built on the foundation of Christ’s blood being the wine of communion.

Of course, all this wasn’t exactly, purely, Catholic. It had a lot of pre-Christian spirit soaked into it as well. And it was also good business. In order to sell wine in the town, a family had to own a vineyard on the heights above. This has led to the situation today, in which Rüdesheim is chock full of restaurants selling poor quality wine to literally throngs of tourists, and the vineyards looking a bit tattered. After all, it’s a lot of work to whip up schnitzels in the kitchen, tend your barrels in the cellar, and then sneak off mid-afternoon to look after your grapes up on the hill, and make it back for Happy Hour.

Drosselgasse

This wine street is the second most-visited site in the entire country. 10,000 people a day.

It doesn’t matter that the wine served to tourists is rather poor here. People taste what they expect to taste. They taste their expectations, the beauty of the landscape and the romance of history, and the gentleness of the waiter or the waitress. Well, the last, if they’re lucky. If you want better wine here, you’d better have a chat with the owner. The good stuff is there only if you know what to ask for.

Tourist Magnet (Rüdesheim am Rhein)

A little romance works like a charm. (See the end of this post for the modern equivalent.)

Still, for all that, something still remains of these social relationships to the land and the notion that we, as humans, connect to it personally, and that when we have a personal connection to that land, we taste it in the wine. There is factor of the air and the light and rain that transfers over. It’s something that the technical researchers haven’t figured out how to measure yet. Humans can, because they’re as physical and immediate as the wine. This process is called art. In the end, you get this:

Loreley

Vineyard in the fall at the Loreley cliffs. On the heights immediately to the north of this vineyard, the mermaids used to sit and by their beauty and their singing lure sailors to their deaths in the whirlpools of the Rhine far below. It made for kind of loud opera, too.

In a country full of national shrines, the Loreley is the one most attached to a sense of the land. This vineyard survives in its marginal corner of the river, because of that connection. To taste this wine, here, is to taste German history, especially that ancient, pre-Christian history that said that men and women came from this soil, where indigenous to it, and could not be separated from it. Myth? Maybe. But just try to tell that to someone who can taste that in the wine.

That’s also what makes the Okanagan wine industry successful. People pay for that. We shouldn’t mess with that by saying nonsense like this:

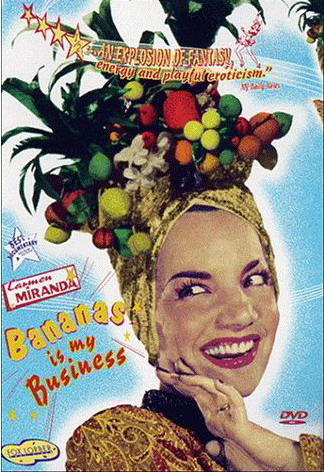

This wine will remind you of Carmen Miranda. Exotic, fruity and the life of the party. Look for ripe apple, pear, delicate honey and a long citrus finish.

And they dismantled the last piece of the German Okanagan and a century of history for that? Without an attachment to the land, it will blow away in the wind. It will last only as long as fashion itself, or as long as the urban-rural connections built by other winemakers remain vital. Oh, by the way:

Sometimes Wine is Fruity

Here in Brno, in Moravia, I’m enjoying the Veltinske Zelene, a wine sharp with green apple-y flavour and a tiny bit of animation. It’s cold here, 10 below freezing, but the wine is as refreshing as anything. Perfect with crisp rolls and cheese at lunch, or risotto at dinner, or even a glass in late afternoon to smooth out the wrinkles of the day. I think this is a wine that would suit halibut, for instance, or prawns. Or on its own on our western deck on the Sechelt Peninsula on a hot summer day as we watch the sun fall behind Texada Island. Is anyone growing these grapes in the north Okanagan?

tk

LikeLike

In German that would be Green Veltliner, I think. A magnificent grape! And, yeah, it should do well here. Especially fine with scallops, I think. When the wine industry embraces its northern locale again, and once again starts sourcing unusual wines, it’ll come. Until then, it’s chardonay. This is, I think, an issue of marketing. The Austrians pull it off, and so do the Saxons in Dresden, and you should taste those Saxon kerners, too. Ours are among the best (and most obscure) whites we grow, but the ones from Dresden, ah, they come out so clear and clean. Marginal climates are sometimes magical.

LikeLike

I’ve since learned that “zelene” means “green”. It’s like drinking cool summer mornings with a little bit of sparkle.

tk

LikeLike