This is a story about truth and reconciliation. The headline says it all.

Many Okanagan Apple Farmers Are Facing This Year’s Harvest Short Handed,

You know, I remember a time, long before the beginning of the world, when journalists sought out facts and were a bit less interested in promoting an agenda out of touch with the details of their subject than some are now. Here are some of the details:

Well, that’s the image I took yesterday. Those bucks are sheltering behind a 12-foot-tall deer fence (They pried it apart with their antlers, into a 5-foot-tall gap.) They are not the only ones. The coyotes have dug a hole to get in and get at them.

So, now we have predators and prey within a fence subsidized by the government to protect a crop on the pretext of protecting the deer, right where a farmer, under B.C.’s Right to Farm Legislation, can shoot the deer without a permit, or invite someone else to do so. This is called entrapment, I think. It speaks of great privilege. Global News might have missed that, but they did get a story about how the COVID-19 pandemic has hurt farmers, like this:

“The travel rules changed and that threw a real wrench into things. As a result, we got 80 to 90 per cent of the workers expected.”

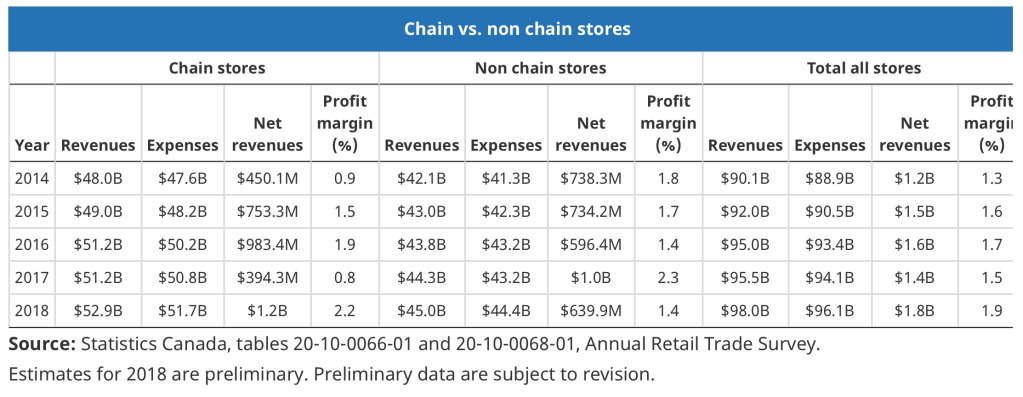

90% is a crisis? 80%? Anyway, the point is, I think, that in an industry surviving on tiny margins, 10% is probably between 5 and 10 times the profit for the year. One might ask, what kind of a crazy business is this, in which an investor plunks in millions of dollars for the privilege of hiring workers from Mexico so that a return of 1% on the money can be made? This kind:

But leave that. Let’s follow Global along.

The situation was even worse on small-scale farms where foreign workers aren’t used due to an inability to meet minimum hour requirements. They rely on a mix of local labour, French Canadians, and even International backpackers, all of whom were in short supply this year.

Here’s how it works: to hire a foreign worker, you have to prove that no Canadian wanted the job. Ads are inserted in local newspapers, offering minimum wage work, 10 hours a day, 6 or even 7 days a week, for 4 – 6 months. There are not many Canadians who would accept such conditions. When that labour pool doesn’t materialize, one brings in foreign workers, who leave their families (the rules are, they must have a family) for 6 months to live in a camp in Canada. But again, let’s leave that and go to Global, who have the news:

“French Canadians have been diminishing in numbers already. Now (because of the pandemic) they drive, instead of fly, and they don’t get around by hitchhiking, so that’s an issue,” he said.

Would you fly across the country for $150 a day? At these rates? As Air Canada quotes, for a one-way trip:

So, like, if you came now and worked for a month, you could spend, like $1500 on airfare. That’s 10 days of your income, right there. Half your income, if you’re getting fewer hours. Some kind of taxation that! Look, French Canadians used to come and pick fruit because there was little work in Quebec, and you got to travel around in a way not possible in Quebec. What’s more, for those who worked hard at piecework forty years ago, when wages were $3.50 an hour, you could make $15 an hour picking apples or cherries. That was enticement to hitchhike across the country. Following this logic, when today’s labour rate is $15 an hour, the apple-picking rate should be $65. Would you fly across the country for that? Maybe. One day of work would come close to paying for your ticket to get there. But what do I know. I just remember a time when history was felt to have some bearing on contemporary events. Now, we get the Global truth:

“And CERB, and low unemployment rates, meant there were many other opportunities for people.”

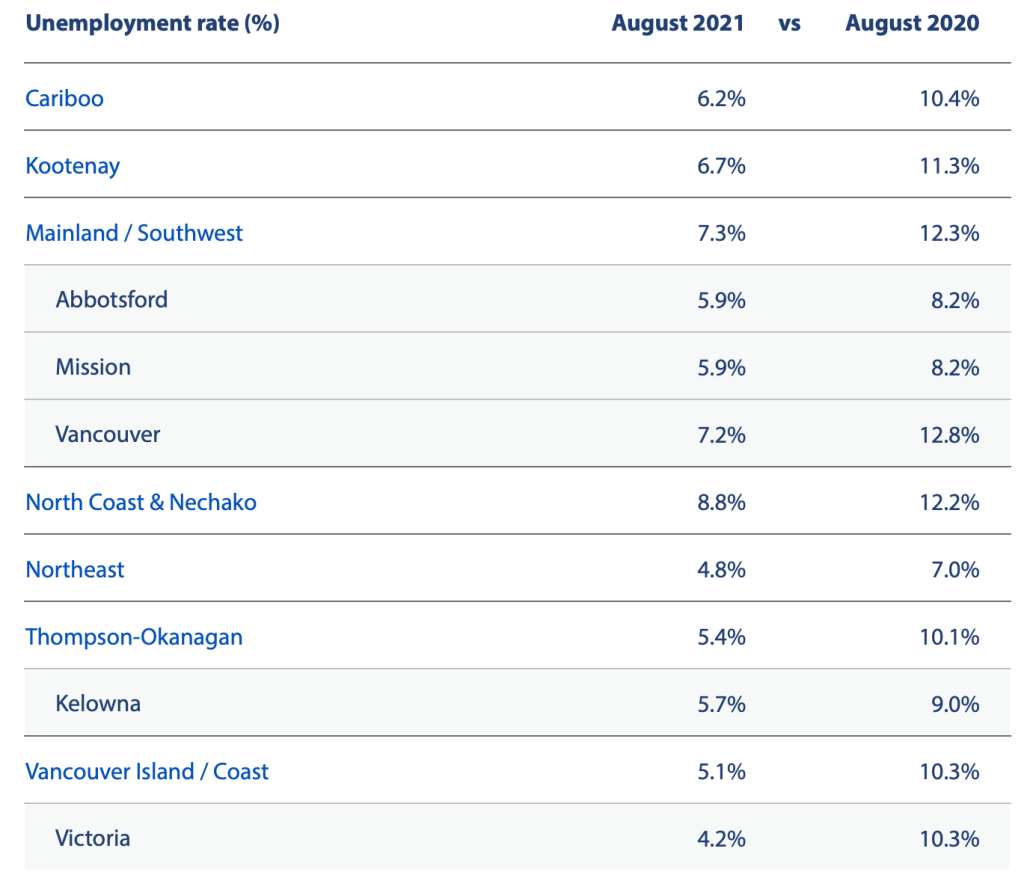

You think so? Have a look at B.C.’s unemployment rates (keeping in mind that 4-5% is considered full employment.)

So, really, there seem to be quite a few of the 5.5 million British Columbians who are out of work. The difference over last year suggests that CERB might not be having much of an effect any more. As for Kelowna, this region, just think of this: if you design your whole economy around building houses to attract elderly people with money, the population is not going to be of working age, and anyone working is going to be serving those retirees. In other words, a 5.7% unemployment rate in the Okanagan might translate to a much higher rate somewhere else. It’s just that they are out-numbered. Perhaps, but Global has the real scoop:

Significantly reduced international travel put a stop to the backpacker pool of labour.

Wow. Just wow. Although it is illegal to work in Canada without a Canadian Social Insurance Number, not an easy thing to get, an International Backpacker is the backbone of the fruit industry! What, are they being paid under the table? Come on, this was a thing back in the 1960s and the early 1970s, with thousands of young people from around the world passing through the valley each day. Thousands worked for my father. At the age of 12, I was crew boss for 100 at a time. They were beautiful. I wanted to join them. But this is not 1970. This is just silly. But what do I know. Well, I know what the industry has to say, which Global has provided:

Got that? It is tough. A grower selling through the packing system (a recent $3,500,000 provincial investment in a new packing facility has “guaranteed” the continued competitiveness of the industry, sure), gets less than it costs to grow the fruit. What the packing house receives, some 48¢ a pound, is about what a farmer needs. The packing cost is prescribed by the government. It’s a great waste, but to change it requires addressing the government and its rules for retail sales, not the grocers. The box the apples come in cost more than the grower receives, for starters, and it is prescribed. As for grocers, look at their actual profits:

Got that? 1.9% profit, not the approximately 75% that the fruit industry graphic suggests. So, what’s going on? Well, let’s ask the orchard:

If the apple is not perfect, in this system no-one can afford to pay to truck it, store it, grade it or pack it. Instead, the $65 an hour wage rate is lowered to $15 to pay for pickers doing the sorting on the farm. As for apple juice that might be made of these “culls”, well, you can buy really cheap concentrate from Brazil, or Argentina, or Turkey, or wherever Indigenous people are growing it, where Canadian pesticide laws don’t apply. All in all…

At this rate, even 48¢ a pound won’t save this farm. And it’s in this bad shape because of an industrial model of farming, requiring massive capital investment (in part a result of land prices set by the retirement housing dream), mechanization, low-paid temporary labour and government subsidies. Global is right to be concerned about farmers, and we’re all right to be concerned about the treatment of temporary foreign workers, but at the sometime let’s not lose sight of the bigger picture: this form of industrial farming doesn’t work. The negative effects are a result of this system and the government rules, subsidies and culture that creates and supports it. That’s not what Global reports, though:

It takes five years for a tree to start bearing fruit worth farming, and if demand increases, there will be a lag.

Back in 1980, I was in this industry, right when the government sent around an expert to explain to farmers how the new type of plantings would start paying in the first year, turn a profit in the second, be in full production, 30,000 pounds to the acre, by the third year, and be fully paid-off and replanted again with new, valuable varieties after year 10. At that time, apples were fetching farmers 12¢ a pound at best, but often 2¢, while the new varieties brought in close to $1. Now those “new” varieties, not replanted or replaced, are bringing in 12¢. This is simple math, however you crunch it. Even so, this “five years” is wrong. Three years would be more fair. Still, that might be the math imported from Holland and five years might be how it works out in practice, especially with current skill levels, but if that’s the case, why on Earth do we continue? So, let’s look at our two bucks again:

See the white plastic? We’re worried about plastic bags in grocery stores, but we can have, literally, millions of square feet of this stuff in an orchard, without a peep. It’s there to reflect sunlight up onto apples grown by the wrong method in the wrong location, because the good land has gone for grapes, the better land has gone for housing, and the fashionable varieties just don’t grow in the areas they are planted on, especially using the methods currently being used, and especially when the pressure to create perfect $1-each apples is all the the industry has left in its effort to survive. In cool fall weather, sunlight will colour apples. It won’t change their bland flavour, though. To fix that, different varieties, grown in different areas, on different trees are required. And to understand how that all came about, consider this historical photograph:

This started out as a plantation culture before the First World War, on par with Kenya and Tanzania. One needed big crews of migrant workers. In the early days, most were Indigenous. Hops, for example, were picked by the Nimíipuu, who came up from Nespelem (south of the 49th Parallel) each year to pick them. The local French and Métis population also chipped in. Look below, though. This is not a particularly young crew.

It was a British agricultural dream, to give the British Middle Class access to Upper Class life.

Someone is going to have to launder those dresses. Just saying.

And when war came, the women were left to do what they could, while their men were being trained to go to France.

More laundering, too.

The women would never see the men again. This settler dream got a leg up by importing European immigrants after both the First and Second World Wars, to replace British losses. The packing houses remained in British hands, and the Europeans, my ancestors included, subsidized the system with their own labour. It was hard, but it was done. The profit came from an increase in land prices, not from food production. Now Global has the latest news on that, too:

“(Farmers have) been scrambling and they’ve had to have their families come in for long hours, seven days a week and it’s been tough on them,” Lucas said.

The question might be, why are we continuing to subsidize such an industry that supports the continued concentration of capital in fewer and fewer hands, while continuing to diminish the human value of labour and the creative potential of communities? Why aren’t we changing our marketing legislation? Why aren’t we educating farmers? Why aren’t we paying a decent wage, when it is possible? One answer might be that settler culture remains attractive in this place and drives such other things as tourism, the wine industry (tourism), and the housing industry, the same one that skews employment statistics. So, when you wake up tomorrow on National Day for Truth and Reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, think of these two bucks and the legislation that has doomed them…

… think of the Indigenous people who are not on this land, and think of this little cherry grove on the hill:

In this settler culture, these high-value choke cherries, which hang on for four months, spreading labour out equitably, which require no water, fertilizer, posts, wires or bank loans, go unpicked. And these ones, right on the orchard fence.

And this variety, also on the fence.

Or these black hawthorns.

Those are Indigenous crops, and they are worth money. Hiring Indigenous people from far, far away to work for low wages is not a fix. What’s ironic about that is that if you figure in the cost of a return flight from Mexico, 2 weeks quarantine in Vancouver, and the cost of housing and busing for workers while here, the $15 an hour paid to these hard-working men looks more like $20 an hour, and for $20 an hour, even $25 if a work-force were trained and tree care were improved, you could hire willing Canadians, even year-round. But that’s not the game, is it. In the spirit of truth and reconciliation, it can be. We can make a better country than this…

… together.

Categories: Agriculture, Ethics, First Peoples, History, Indigenous Farming, Land, Land Development, News, Other People, Spirit, Urban Okanagan

What an eye-opener this post has been. I learned a lot. Thanks for posting. Best, Babsje

LikeLike

It’s like my personal brick wall!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can understand that!

LikeLike

Well done, Harold. You put a lot of work into this. Thanks Brian

LikeLike

Thanks, Brian! I must admit, I saw that article and I thought, OK, here’s one I guess I have to spend a night and a day on, if no one else is going to. There’s so much more to say, as you know. I’ve been watching this orchard fail since day one. I was close friends with the Japanese Canadian woman who reluctantly sold it to them. And those deer, I’ve known them since they were wobbly kneed! “Oh, brother, it’s Harold with his camera again,” I’m sure they groan to themselves!

LikeLike

Thank you for this post. We can grow all the apples we’d ever need in the Bulkley Valley; we don’t need stick-tree-fruit.

LikeLike

Darned rights! Yours will taste better, too. Plus, you get to thwack the bears to convince them to share. All good.

LikeLike