Today, I’d like to show you some water in its living environment and some crazy water. First, living water:

That’s mock orange, doing its thing. Home to deer, porcupines, bears, lazuli buntings, people, American goldfinches, chickadees, finches, quail, crows, pheasants, fritillary butterflies, swallowtails, yellow-bellied marmots, meadow voles, coyotes, wolves, magpies, northern flickers and everyone else who still manages to survive on this ruined grassland. Now for some crazy water:

I showed you this image of the bear I spooked out of the mock orange the other day, but it bears (ha ha) repeating in this context, because that’s not a natural landscape it is walking through. It is, actually, something much like this:

Syrian government officials walk on a road, back dropped, by damaged buildings from fighting with Free Syrian Army fighters in the old city of Homs, Syria, Thursday, May 8, 2014. Syrian President Bashar Assad’s government in the north prepared to regain control of the central city of Homs following last week’s cease-fire agreement after a fierce, two-year battle with the rebels trying to oust him. (AP Photo)

Look at it again, if you please:

This is a ruin from a war over the land fought unevenly over the last 160 years between the valley’s syilx people and various industrial farmers. By 1871, the land was trashed by overgrazing born of ignorance. What you see here, a chokehold of big sage interspersed with invasive cheatgrass, both of them useless in these numbers for supporting complex nets of life, are replacements for a rich grassland that flowed with life through the year. The rich grassland was a creation of a partnership between the earth and the syilx. Its trashing was an act of aggression: ignorant, for the most part, but aggression nonetheless. Still, a small amount of life survives in the ruins: voles, and the coyotes, bears and hawks who hunt them, all dependent on the lighter-coloured plants you see above, the arrow-leafed balsam root, a kind of wild sunflower that has adapted to the ruins and is recolonizing them. That is a vision of hope: a ruin, sure, but hope nonetheless. Note how much water these flowers represent, and how much of it flows through a renewable web.

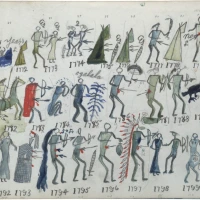

Below is some more water from the war. This is Chief Emmitt Liquatum of Yale in1881.

Photo: BC Archives.

Note the top hat, a symbol of power from the fur trade days (or at least of a ritual belief in power). It is a beaver turned to felt.

Beaver Keeping the Water in the Sinlahekin Valley

Beavers ensure a balanced distribution of water in dry country but were trapped and traded, often before the first European colonists showed up, for war surplus Napoleonic rifles, in an attempt to stave off genocide. It worked, but barely, and more because of the top hats and pre-Canadian relationships than the rifles. The image of Liquatam  was taken shortly after the salmon fishing on the Fraser River, the main food source of his people for 6,000 years, was rendered illegal by the new Canadian government (of 1871 in these parts), to support White salmon fishermen on the coast. I have another image (a bit farther down), which shows the crazy water that comes from this nonsense. It is an image of the north end of 350-square-kilometre-135-kilometre-long Okanagan Lake in this year’s high water. It has been poisoned. This has come about in part because of those dead beavers and the industrial agriculture made possible by their absence, and the private, industrial property aesthetic that presumes prominence for industrial uses of water and land over health of water and land for people and all creatures, and a lack of run-off. All these workings-out of old errors and privatization is now showing itself in this form:

was taken shortly after the salmon fishing on the Fraser River, the main food source of his people for 6,000 years, was rendered illegal by the new Canadian government (of 1871 in these parts), to support White salmon fishermen on the coast. I have another image (a bit farther down), which shows the crazy water that comes from this nonsense. It is an image of the north end of 350-square-kilometre-135-kilometre-long Okanagan Lake in this year’s high water. It has been poisoned. This has come about in part because of those dead beavers and the industrial agriculture made possible by their absence, and the private, industrial property aesthetic that presumes prominence for industrial uses of water and land over health of water and land for people and all creatures, and a lack of run-off. All these workings-out of old errors and privatization is now showing itself in this form:

You are looking here at a toxic algal bloom on the Okanagan Indian Reserve at Head of the Lake — more specifically at the water off a recreational property leased by a band member to a White family. No-one wants to swim in industrial sludge, but that’s what this is. Here’s the story: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/algae-bloom-okanagan-lake-1.4178423. Here is, incredibly, what the story says:

The Okanagan Indian Band released a warning on Sunday to residents and visitors to stay out of the north arm of B.C.’s Okanagan Lake until further notice due to a toxic algae bloom.

The band says the bloom in waters off its land was first thought to be a sewage leak, but testing showed it was caused by a high level of organic material in the lake.

High temperatures over the weekend helped the algae flourish in a soupy mixture that the band says includes everything from burlap and sand debris to sewage, grass, leaves and dead animals.

They are being kind. Here’s some crazy water — in the old lake bed to the north of the lake by the looks of it but perhaps in the old lake bed to the east of the lake:

This is about privilege, even though it seems to be about work and economy and making a country. The thing is, before that country set the industrial terms for water use, water was a common good, shared by all. After 160 years of an uneasy balance between sharing and industrial water rights, filtering water through industrial crops before it flows into the lake, and the old syilx water system it represents, continues the original violence. There’s no way of covering that up, because ignorance is no longer an excuse. Sure, there appears to be a belief that if contaminated water is passed through soil, which is viewed as part of the de-indigenized cultural space called land, which has the other names of earth and nature, it will be again as pristine as the original White impression of indigenous/earth cultural creation in 1858, when all this began. That is crazy. First, because this so-called “nature” was a humanly-maintained cultural space, which gave the earth cultural autonomy, and secondly because the following image isn’t pristine:

It’s the lake bottom in the west arm of the lake, that’s what it is, just south of the algal bloom on Okanagan Indian Band shores which I showed you above, and right beside one of the Okanagan’s major swimming beaches, to which thousands of people come with their children every summer to enjoy what is, hopefully, “the good life,” and why not, family is really important. Here are some images of this arm of the lake…

So is the image of pristine water poisoned by industrialization below. It connects to beach culture, and the recreation use of Okanagan Indian Band lands, through a direct colonial desire to physically enjoy nature. In this case, it is through industrially-management of land, draining water down off the hills, to produce pumpkins for a European harvest festival. This work is done with a mixture of herbicides, fertilizers, cultivated weeds (the things are attempting to heal the soil, yet they are tilled under as they don’t fit the imposed industrial model) and water and sun managed by plastic, thrown away at the end of the season. This is an image from last year This year, this land is empty, except for a trial plot of genetically-modified canola under scientific trial. That the land was removed from life to produce this hyper-industrial product is, I’m sorry, in it context there’s no other word for it, an act of pure aggression and violence. That syilx water flows through it.

Okanagan Basin Water Board, are not absolved of blame just by saying good things.

“Our vision is to have a fully-integrated water system, meeting the needs of residents and agriculture while supporting wildlife and natural areas.”

Here’s their image of that:

It’s weird to have one’s valley turned into a cartoon, but note some important things: first, the 10,000-year-old lake of fossil water from the Ice Age is labelled “waste water”, and the river systems are labelled “municipal water” and “water supply” completes a cycle with “waste water.” That’s disrespectful of the bear I met the other day, the syilx, and anything else that comes from this land. In this conception, there is only urban infrastructure, based on colonial water use models. You can see the contrast between desert and lushness in the image of my city, Vernon, below:

This elite blindness is omnipresent and is a sign of ecological poverty. It comes from an intellectual culture that views, without question, this spring’s problems with water in the valley as problems of extreme high water. Seemingly, if the land had just soaked it up a bit better, like we were used to last year, it would not get nuts like this. Well, it’s not the first flood. Blaming water run-off on weather, when the land’s ability to use water or hold it has been removed, is intellectual nonsense. Worse, when a cause is given, it is global warming. Global warming is serious stuff, but this is the result of the abuse of human-earth water systems, based on an ignorant or dismissive rejection of syilx cultural values, people and knowledge, over anything else. To say otherwise is crazy. The history is very clear. I wish the craziness stopped there, but here’s some more crazy water, and once again it is crazy with the best of intentions and the worst of blissful ignorance and disrespect:

This is an image of vineyards, formerly the orchards of my youth, in Naramata, looking towards the southern shores of Okanagan Lake, where any muck from the north will eventually flow, before co out through the Okanagan River, in the middle distance of the image, and joining in that dredged, diked channel…

…with the outflow from the Penticton Waste Water treatment plant, before continuing south. It is the poster image of an article on a new water study being conducted at the University of British Columbia in Kelowna, at the approximate mid-point of the lake. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/could-soil-be-the-next-carbon-sink-ubc-okanagan-to-lead-study-1.4152301

The study, worth $1,400,000, is to determine some pretty useful stuff around the role irrigation water plays, including the rates at which dirt, in a hot climate, builds up carbon — not to protect the atmosphere from industrial pollution but to become soil, which is carbon=based life and dead life on which it feeds and which holds its water — under the effects of irrigation. The difference between the agricultural capacity of the soil before and after irrigation would be useful to know, especially since the early irrigated desert cultures of Mesopotamia poisoned their soils with the salt that comes from evaporation during irrigation and turned their gardens into deserts, which are now battlefields in hopeless and helpless wars, not to mention contemporary experience with the same issue in the American Southwest, in order to modify irrigation, but that’s not how the story is told. The media tells it like this:

“When we talk about climate change, we often discuss the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. But actually a huge amount of carbon is stored in the soil,” Kirsten Hannam, a research associate on the project, told CBC’s Chris Walker on Daybreak South.

The buildup happens when carbon dioxide in the air is fixed by plants during photosynthesis and converted into leaves and roots. The carbon is deposited into the soil and accumulates over time.

That, unbelievably, is a description of life on earth: carbon, deposited and accumulating over time. How disrespectful. How obscene. But it’s not just the media. Here’s how the government sees it:

“These new investments are part of the government’s commitment to addressing climate change and ensuring our farmers are world leaders in the use and development of clean and sustainable technology and processes,” said

Lawrence MacAulay, minister of agriculture and agri-food in a statement.

Got that? The government is going to address global climate change by using scarce and incredibly precious water, already over-committed by overpopulation of humans, in the Okanagan Valley, and is selling this as a way for farmers to develop clean and sustainable processes. I think this means is that farmers will be using our water to sequester industry’s carbon, and will be paid to do that, instead of producing food, or learning to work with beavers, or respecting the syilx. Really, this has to stop. The spring has been rife with young Indigenous writers demanding that the violence stop, and calling out the White community on their sense of entitlement. Well, it’s not about statements of social inclusiveness. It’s about changing the story so that the story is a syilx, or a secweopemc, or a cree story, and that’s going to mean that the earth and her creatures, and non-industrialized, non-privatized water are going to have to be at the centre of law and ethics. Anything else is absolutely stark raving mad.

We either stand with the earth and her people or we shoot it in the temple. The problem is: we are her people. The solution, which is easy, is that we are of her water, and we need to go home.

Categories: Erosion, Ethics, First Peoples, Grasslands, Industry, Water

I am pondering this article carefully, and it takes careful pondering, but do you have special knowledge to identify this toxic algae bloom as at Head of the Lake? To my knowledge, the Band has not identified the exact location of this bloom except to say the North Arm of the lake. I would be very interested to know your source. Thank you Harold.

LikeLike

My bad, perhaps, but I take “head of the lake” to be the north arm, north of the “head of the lake” at the end of the “turtle ridge” stretching from turtle mountain to its end and across from “turtle point” which marks the other entrance to the west arm of the lake. Anything north of there I’d call “head of the lake”, given that Napoli’s mission was said to be at “head of the lake”, near the present RC church, a long way from spall golf course which is at “head of the lake” now. So, the north arm. As for the exact location, I’d follow the currents. All that flood debris in question is going to be coming from overwhelmed agriculture. There’s very little of that, in flood’s way, in the main body of OIB land. Or am I wrong?

LikeLike

“All that flood debris in question is going to be coming from overwhelmed agriculture.”

I would argue that the flood debris in question is generated locally from the flooded, privately leased, OKIB properties not from agriculture. Head of the Lake, when capitalized, refers to a specific location including the HOL hall and church.

LikeLike

ah

LikeLike

They mention in today’s paper that some comes from Deep Creek.

LikeLike

You describe a spiritual poverty that infects every aspect of our life on this planet. If I understood your argument correctly you are calling on us to learn how to tell our story from a perspective different from the stories that we tell currently from our current perspective of economic growth. Just before reading your post I read an article on social mobility in the UK in The Guardian that noted that 30% of children in the UK currently live in poverty. I don’t think that the two things are unrelated. That is to say that I think that poor children in the UK have more in common with bears in the Okanagan than they do with a model of the economy that excludes both from being fully alive. I think the same goes for wage slaves in the majority of our enterprises and even the bright young people who give up their souls for the remuneration packages of our financial service industries. To tell the story from the perspective of the bear seems to hold the potential of liberating all of us from our misery.

LikeLike

Yes, you understand correctly, and thank you for taking the time to read the article and doing so. I was in Switzerland when the whole thing blew up this spring about Indigenous rights and writing in Canada, which was painful: to be so turned on my head, at such distance. Then one young Indigenous woman entered the debate with the astute comment that non-Indigenous people could support Indigenous people by fighting with them against White privilege, as opposed to the more general Canadian stance for support, which is to accept one’s eternal ignorance and give all public space to Indigenous voices, which is, of course, a White cultural response and unpalatable. That was a light in the darkness for me and a true gift. Coupled with my spring readings on Indigenous slavery <> and my ongoing writings to learn to speak the innate Indigenous language within English, I managed to put together 3 manuscripts last week, all of which date back to a series of notes I wrote 16 years ago, when the towers burned in New York. Now I have a ms linking my trips on the camino through Germany, my trips through Iceland and my reading of Gunnar Gunnarsson, and my poetic experience, and it finally works. With that background, I found I had the eyes, at last, to see the bear. It’s exciting that you made the connection to children (our rates are 1 in 4, still awful.), as it began with teaching writing to impoverished children on a remote Indian reserve in British Columbia, and my total frustration (i could say disgust) with the British Columbia Ministry of Education and its failure to address their needs. After a long journey gathering the tools with which to speak of this failure clearly, it seems we are here together having this conversation. Your observation is powerful, and it comes at exactly the right time. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am greatly moved by what you write here. It was not my intention to write anything that might be described as “powerful” or even helpful. Perhaps that is the best way. It was just as I read your post that it struck me that if I were to see reality even for a moment through the eyes of a bear, I would have to achieve a kind of self forgetfulness, the same kind of self forgetfulness that is required to see the connection to children in poverty.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, environmentally embedded, perhaps. In terms of neuroscience, children develop brain pathways in response to environment, which are then hardwired at puberty, making us all unique (on a common ground, of course.) In terms of environmental science, ecosystems are organic balance systems, with all parts being one within the whole. That being said, perhaps we are looking at children and bears who are responding organically to non-organic systems; their organic systems look for organic pathways out of the fence, but pathways that include the fence within them. I sat in the middle of the old East German border one day and cried at the pointlessness of the wall within my own head, at how pointless it all was, now that it was reduced to a field of wildflowers, ants and bees in the sun. It is possible to take down the fences. They are both within and outside of us. As you know, I’m sure. I’m re-reading R.S. Thomas these days. He is very wise on a lot of this stuff. It is very moving to work through his poems day by day.

LikeLike

This is a very moving post, Harold. Thank you. You help me, and others to see in new/old ways. So needed. Was there any form of wild apple there before settlement? Ruth

LikeLike

Hi,

the coastal peoples had wild apples, a minor crop. In the interior, it was black hawthorn and columbia hawthorn.

Apples are the indigenous crop of my people, who were also, of course, indigenous, and that knowledge is still there. Patenting apple varieties and GMO manipulation is as much a sin against Indigenous wealth as stealing secwpepemc (for example) medicinals remains today. There is great commonality.

Best

Harold

LikeLike